I wrote a profile of minimalist composer, philosopher and blues musician Catherine Christer Hennix for The Wire last year to coincide with the release of her masterwork from the 1970s, The Electric Harpsichord. Hennix lives in Berlin these days, and has a band called The Chora(s)san Time-Court Mirage which played a series of shows this summer at the Grimmuseum. The band features the amazing Amelia Cuni, to my mind the foremost practitioner of Hindustani classical vocal music outside of the south Asian diaspora, and a master of the most austere of classical vocal styles, dhrupad. You can hear a twenty minute recording of Hennix et al on Soundcloud — the first time that anyone not living in Berlin has had a chance to hear these guys. The most obvious comparison of course is the Theater of Eternal Music, especially in later days when La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela were using sine waves, and were joined by folks like Jon Hassell. But Cuni doesn’t “just” sustain a drone tone, she moves between notes in the style of an alap singer. And there’s something about the way the sound pulsates, in a way that’s almost monstrous, that’s peculiar to Hennix. At times you can’t tell whether the sound is happening externally or actually inside your skull. The sound seems to surge, but the surge is, well, mathematical, not in the sense of something cold or formal, but in the sense of an iteration that extends to infinity … you can somehow feel or maybe hear the matrix of tones beyond what’s actually audible.

Search Results for: hennix

The Politics of Vibration: Music as a Cosmopolitical Practice

The universe vibrates. The Politics of Vibration: Music as a Cosmopolitical Practice, published by Duke University Press in summer 2022, sets out a model for thinking about music as emerging out of a politics of vibration. It focuses on the work of three contemporary musicians — Hindustani classical vocalist Pandit Pran Nath, Swedish drone composer Catherine Christer Hennix and Houston-based hip-hop creator, DJ Screw, each emerging from a different but entangled set of musical traditions or scenes, whose work is ontologically instructive. Three musics characterized by slowness, much of the time then. From these particular cases, the book expands in the direction of considering the vibrational nature of music more generally. The book looks at a variety of musical examples including a Ryan Driver/Sandro Perri concert in a park in Scarborough, ethnomusicologist Jose Maceda observations concerning traditional Philippine musical instruments, Sri Karunamayee’s mental ladder of scales, Keiji Haino’s ideas of vibrational space, love and death according to Prince, Frankie Knuckles’ first visit to The Loft, Moroccan gnawa musicians in the Djemaa al Fnaa in Marrakech, John Coltrane’s famous sleevenotes to A Love Supreme, Earl Sweatshift’s alchemization of depression, and a performance by flamenco/folk master Peter Walker.

Vibration is understood in multiple ways, as a mathematical and a physical concept, as a religious or ontological force, and as a psychological/psychoanalytic determinant of subjectivity. The organization of sonic vibration that is determinant of subjectivity, a.k.a. music, is understood to be pluralistic and modal — and topological rather than phenomenological or time-based. And understanding what music is means shifting our understanding of what space is. I argue that music needs to be understood as a cosmopolitical practice, in the sense of the word “cosmopolitics” recently introduced by Isabelle Stengers — music can only be understood in relation to the worlding and forms of life that are permitted in a society, and according to decisions that a society makes concerning access to vibrational structure. I reconsider the ontology of music in the light of the practices of contemporary musicians, and I try to open up what the possibilities for a free music in a free society would be.

Even after finishing writing the book, I still find it hard to describe what I’ve written. The above paragraph is one version of it — and describes a kind of philosophical project, but the book is a lot more personal than that, since it also describes my own life, participation in different music scenes, shit that has happened, to me and those around me. And above all, the book also describes a kind of apprenticeship in music and philosophy via my introduction to the music of Pandit Pran Nath in the late 1990s, and the music and philosophy of Catherine Christer Hennix, who was a student of Pran Nath’s, in the early 2000s. While Hennix’s work has recently gained some attention thanks to Blank Forms’ publication of her selected writings in Poesy Matters/Other Matters, and various archival and new audio releases, the full complexity of Hennix’s brilliant ideas and sonic practices has not until now been documented. Hennix’s work is challenging and requires study and attention to understand her full vision of what music, mathematics, sound and ontology can do. In this book I describe my own studies and conversations with students of Pran Nath’s — and years of study and dialogue with Hennix. And I apply Hennix’s insights to musical worlds different to her own — showing how versatile and powerful and challenging her ideas are. What emerges is an idea of music as pragmatic but cosmopolitically entangled improvisation in a universe made of vibration. I explore these ideas in relation to the Black radical tradition and Houston based DJ Screw’s chopped and screwed sound. This book is also my own improvisation, in words, in that entangled universe. It is also about breaks, breaks in symmetry which give everything their particular finite forms, musical breaks and the power of repetition, mathematical modelling and its intersection with human fragility and finitude, but also the incredible breakage of/in my own world, the music scenes that I find around me, and in the lives of musicians who have cosmopolitical ambitions. This book offers a broken ontology of music — and I still don’t know if it could be otherwise.

You can read the introduction to The Politics of Vibration here!

I made a playlist of tracks and films related to the book for Duke’s blog — I also went into some of the ideas that the book explores, and I think it’s a useful primer for the whole project.

And I curated a mix of sounds related to the book for Seance Center’s excellent monthly NTS radio show — you can also listen to it on Soundcloud!

I did a wide ranging interview with Scott Stoneman for his Pretty Heady Stuff podcast — we got into everything from the sonics of bad breakups to Pharoah Sanders’ (RIP) recent recording with Floating Points. And another great interview with journalist Yannis-Orestis Papadimitriou for his Archipelago podcast on Stegi/Movement Radio.

Here are the blurbs for the book:

“Marcus Boon models the perfect combination of rigor and imagination. In this daring and original book, he approaches vibration through mathematics, physics, and psychoanalysis to articulate an ontology of music based on space over time, frequency over duration, instantaneity over progression. The ease with which Boon pursues his ideas across experimental music, Indian classical singing, and recent hip-hop flashes an exciting glimmer of one future for music studies. With The Politics of Vibration, we are already there.” — Benjamin Piekut, author of Henry Cow: The World Is a Problem

“Vibrations change your life; vibrations make life. Marcus Boon explores the hidden practices of vibrations for an original and fascinating insight into the nature of musical experience. In a uniquely sensitive manner—personal and political and philosophical at the same time—he weaves his way through the pulsating energies of Indian classical singing, drone music, minimalist avant-garde, and chopped and screwed hip hop. Boon gives equal attention to the big names and the little known, as they meet in cosmopolitics between the global South and North.” — Julian Henriques, author of Sonic Bodies: Reggae Sound Systems, Performance Techniques, and Ways of Knowing

Berlin, 2022-2023

For the academic year 2022-23, I will be a Research Fellow at the University of Potsdam, in the Minor Cosmopolitanisms RTG. And I will be living in Berlin. The Minor Cosmopolitanisms research group is a wonderful and very unique crew of people engaged in research on countercultural, subaltern and other formations around the world. I’ve been involved with the group as a dissertation supervisor since the group’s inception about a decade ago, and before that on some of the group’s earlier projects, including the Postcolonial Piracy conference and book. I’m fortunate enough to have a sabbatical year and will be working on some new projects, including a book on waves, a short book about the history of the idea of practice, considered globally, and potentially a book on transnational Buddhist poetics. Work on The Third Mind continues, slowly but surely. And I am also working on a book about space with my mentor/friend Catherine Christer Hennix.

The Politics of Vibration: Music as a Cosmopolitical Practice

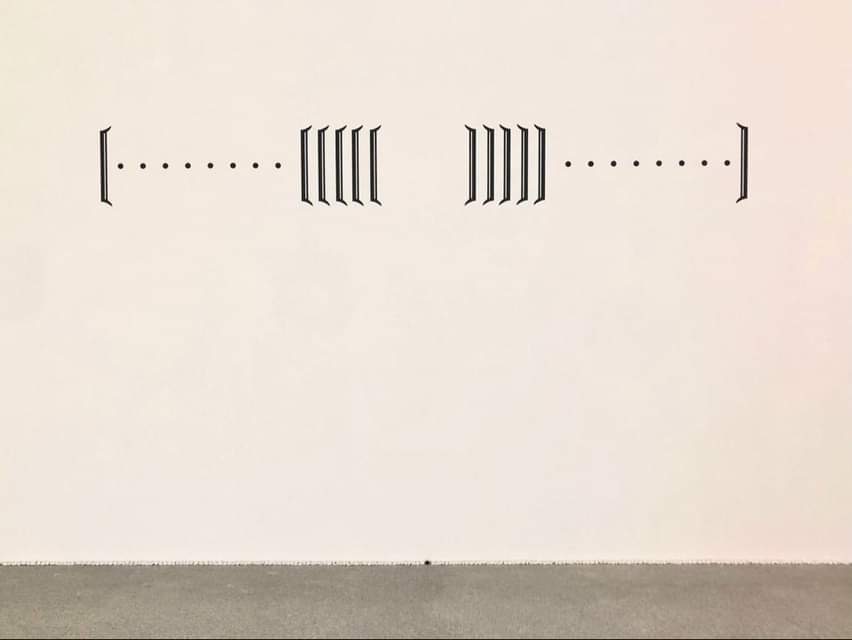

“The (MA-) Gap Theorem [Re : Yoga-57/L’etourdi]” 2021

Photo: Amadeo Schwaller

The universe vibrates. My new book, The Politics of Vibration: Music as a Cosmopolitical Practice, which will be published by Duke University Press in summer 2022, sets out a model for thinking about music as emerging out of a politics of vibration. It focuses on the work of three contemporary musicians — Hindustani classical vocalist Pandit Pran Nath, Swedish drone composer Catherine Christer Hennix and Houston-based hip-hop creator, DJ Screw, each emerging from a different but entangled set of musical traditions or scenes, whose work is ontologically instructive. Three musics characterized by slowness, much of the time then. From these particular cases, the book expands in the direction of considering the vibrational nature of music more generally. The book looks at a variety of musical examples including a Ryan Driver/Sandro Perri concert in a park in Scarborough, ethnomusicologist Jose Maceda observations concerning traditional Philippine musical instruments, Sri Karunamayee’s mental ladder of scales, Keiji Haino’s ideas of vibrational space, love and death according to Prince, Frankie Knuckles’ first visit to The Loft, Moroccan gnawa musicians in the Djemaa al Fnaa in Marrakech, John Coltrane’s famous sleevenotes to A Love Supreme, Earl Sweatshift’s alchemization of depression, and a performance by flamenco/folk master Peter Walker.

Vibration is understood in multiple ways, as a mathematical and a physical concept, as a religious or ontological force, and as a psychological/psychoanalytic determinant of subjectivity. The organization of sonic vibration that is determinant of subjectivity, a.k.a. music, is understood to be pluralistic and modal — and topological rather than phenomenological or time-based. And understanding what music is means shifting our understanding of what space is. I argue that music needs to be understood as a cosmopolitical practice, in the sense of the word “cosmopolitics” recently introduced by Isabelle Stengers — music can only be understood in relation to the worlding and forms of life that are permitted in a society, and according to decisions that a society makes concerning access to vibrational structure. I reconsider the ontology of music in the light of the practices of contemporary musicians, and I try to open up what the possibilities for a free music in a free society would be.

Even after finishing writing the book, I still find it hard to describe what I’ve written. The above paragraph is one version of it — and describes a kind of philosophical project, but the book is a lot more personal than that, since it also describes my own life, participation in different music scenes, shit that has happened, to me and those around me. And above all, the book also describes a kind of apprenticeship in music and philosophy via my introduction to the music of Pandit Pran Nath in the late 1990s, and the music and philosophy of Catherine Christer Hennix, who was a student of Pran Nath’s, in the early 2000s. While Hennix’s work has recently gained some attention thanks to Blank Forms’ publication of her selected writings in Poesy Matters/Other Matters, and various archival and new audio releases, the full complexity of Hennix’s brilliant ideas and sonic practices has not until now been documented. Hennix’s work is challenging and requires study and attention to understand her full vision of what music, mathematics, sound and ontology can do. In this book I describe my own studies and conversations with students of Pran Nath’s — and years of study and dialogue with Hennix. And I apply Hennix’s insights to musical worlds different to her own — showing how versatile and powerful and challenging her ideas are. What emerges is an idea of music as pragmatic but cosmopolitically entangled improvisation in a universe made of vibration. I explore these ideas in relation to the Black radical tradition and Houston based DJ Screw’s chopped and screwed sound. This book is also my own improvisation, in words, in that entangled universe. It is also about breaks, breaks in symmetry which give everything their particular finite forms, musical breaks and the power of repetition, mathematical modelling and its intersection with human fragility and finitude, but also the incredible breakage of/in my own world, the music scenes that I find around me, and in the lives of musicians who have cosmopolitical ambitions. This book offers a broken ontology of music — and I still don’t know if it could be otherwise.

About

I am a writer, journalist and Professor of English at York University, Toronto. I’m also a member of that university’s Social and Political Thought program.

I am a writer, journalist and Professor of English at York University, Toronto. I’m also a member of that university’s Social and Political Thought program.

I grew up in London to English and German parents and came of age during the punk era, turned on by hearing “Anarchy in the UK” on pirate radio one night in a bedroom in the suburbs, and by a recording of John Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things”, also heard in that same bedroom. I studied English literature at University College London, while writing reviews for the New Musical Express, DJing warehouse parties, and making trips to New York where I encountered the splendorous world of NYC hiphop, graffiti, Afrika Bambaataa, electro and other dance scenes.

I moved to New York in 1987, working as a freelance writer. For much of the 1990s, I was involved in AIDS activism, writing for the PWA Coalition’s journal, participating in Act Up’s Treatment and Data Committee, and working for several years at the Community Research Initiative on AIDS as an assistant to the great AIDS researcher Joseph Sonnabend. I wrote an SF novel Brain Forest, a devastating but unpublishable allegory about the AIDS crisis, and received a PhD in Comparative Literature from New York University, where I worked with anthropologist Michael Taussig, cultural theorist Andrew Ross and literary theorists Avital Ronell, Richard Sieburth and Jennifer Wicke. My dissertation, The Road of Excess: A History of Writers on Drugs, was published by Harvard UP in 2002.

My second full length book In Praise of Copying was published by Harvard University Press in October 2010.

Since moving to Toronto, I have continued to write about music and sound for The Wire, and about yoga, Buddhism and other spiritual traditions for Ascent. I was also one of the four members of the MAMA DJing crew, who ran an awesome party devoted to emerging global dancehall rhythms at Senegalese nightclub Teranga, and underground space DoubleDoubleLand in Toronto from 2009-2012.

I collaborate with my wife/partner Christie Pearson as TheWaves on immersive vibratory environments of various kinds: we created the now infamous all night swimming pool installation/party Night Swim for Toronto’s first Nuit Blanche in 2006, an all day celebration of Toronto’s forgotten histories of public bathing Fire in the Water at Sunnyside Bathing Pavilion in 2012, and our first full vibratory environment at University of Tasmania School of Art in Hobart in 2015.

I was part of Cornell University’s Society for the Humanities study group on sound in 2011-12, and I am currently finishing work on a book entitled The Politics of Vibration, which attempts to expand the philosophical bases of sound studies in the direction of practices of vibration and energetics. The book (which Duke UP published in August 2022) has chapters on Pandit Pran Nath, Catherine Christer Hennix and DJ Screw.

In 2015, the University of Chicago published Nothing: Three Inquiries in Buddhism, co-written with Eric Cazdyn and Timothy Morton. This is my first attempt to write about Buddhism, and to argue the importance of Buddhist philosophy and practice in contemporary philosophy and everyday life.

In 2018 I published an edited collection on the topic of Practice, with Gabriel Levine, in the Whitechapel Gallery’s Documents of Contemporary Art series. I am currently working on a related book entitled Practice: Aesthetics After Art.

I am currently working on two other book projects: one a new edition of William Burroughs and Brion Gysin’s The Third Mind entitled The Book of Methods (which the University of Minnesota will be publishing), edited with Davis Schneiderman; the other a book of conversations about the concept of space with mathematician/composer Catherine Christer Hennix.

Talks

Current/Upcoming:

Nov. 12, 2022. Book launch for The Politics of Vibration at the Minor Cosmopolitanisms Assembly, silent green, Berlin. In conversation with Siddhartha Lokanandi.

Nov. 1, 2022, “Listening to Vibrational Space with Pandit Pran Nath, Catherine Christer Hennix and DJ Screw”, Goldsmiths’ Center for Sound Technology and Culture, London.

Past:

Sept. 30, 2022. “The Untimely Third Mind” w. Davis Schneiderman. European Beat Studies Network conference. Murcia, Spain.

May 30, 2022. “The Gap: Chogyam Trungpa’s Buddhist Poetics”. American Literature Association. Chicago.

Oct. 30, 2021. “The Book of Methods”, w. Davis Schneiderman. European Beat Studies Network Conference. Online.

Oct. 10, 2021. “Hennix/Lacan”. Cast-off: A Discussion of Lacan and the Arts, w. Tim Themi, Vanessa Sinclair and David Schwartz. Online.

Feb. 5, 2020. “Vibration-In-Itself: Sound, Humanism and the Anthropocene”. University of Warwick, UK. Sounding the Anthropocene lecture series.

November 16, 2019. “Vibration in Itself: Modal Approaches.” Tuning Speculation conf. Toronto, Canada.

October 25 – 27, 2019. Panel on Buddhism, Art and Social Justice. In the Present Moment: Buddhism, Contemporary Art, and Social Practice, organized by the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria

December 6, 2018. “Sonic Practices”: a conversation with Julian Henriques. Minor Cosmopolitanisms conference, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Germany.

July 26, 2018. “Practice qua Practice”, a conversation with Christie Pearson and Antariksa. KUNCI Cultural Studies Center, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

May 31, 2018. “What is a Practice?” a workshop/panel celebrating the Toronto launch of Practice book, featuring Sameer Farooq, Rea McNamara, Diane Borsato and Su-Feh Lee discussing what it means to practice, University of Toronto Art Center.

April 28, 2018. “What is a Sonic Practice?” A workshop/listening session for the launch of the Practice book at the Hopscotch Reading Room, Berlin, Germany.

April 26, 2018. A conversation with Kader Attia, Nina Power and Gabriel Levine, for the launch of the Practice book, co-edited with Gabriel Levine, at Whitechapel Gallery, London, UK.

March 27, 2018. “Poetry as Linguistic and Vibrational Practice: Some Buddhist Variations”, ACLA Annual Meeting, Los Angeles.

Feb. 18, 2018. An introductory talk on Catherine Christer Hennix’s work, followed by a conversation with her to celebrate her retrospective exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. Watch here.

Nov. 18, 2017. “Music and the Continuum”, Tuning Speculation V, Toronto.

October 12, 2017. “Replica, Originality and the Art of Devotion.” Panel with John Giorno, Ariana Maki and Tsherin Sherpa. Hunter College Art Galleries, New York, NY.

April 28, 2017. “Gilbert Rouget’s Music and Trance and the Politics of Vibration”, Music’s Pluralistic Potential conference, Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany.

March 18, 2017. I will be interviewing Catherine Christer Hennix onstage as a part of the MaerzMusik festival in Berlin.

October 24, 2016. “In Praise of Copying”, keynote talk at the Multiple Museum Practices: Museum as Cornucopia Conference, U. Oslo, Norway.

March 21, 2016. “Vanguardas, Underground e Pirataria” (“Avant Gardes, Undergrounds and Piracy”). Institute for Technology and Society, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Jan. 31, 2016. Panelist on “Piece – Presence – Practice: Aggregate States of Global Sound Artifacts” at New Geographies of Sound Art conference, Club Transmediale 2016, Berlin, Germany.

Nov. 22, 2015. “Design Principles for Immersive Vibratory Environments”, w. Christie Pearson. Tuning Speculation III, Toronto, Canada.

Oct. 9, 2015. “Chopped and Screwed, Slowed and Throwed: DJ Screw’s Politics of Vibration”, American Studies Association meeting, Toronto, Canada.

Sept. 9, 2015. “Immersive Vibratory Environments as Social Practice,” a workshop with Christie Pearson, Tasmanian College of the Arts, Hobart, Australia.

Aug. 14, 2015. “Thinking Energy in Contemporary Theory and Popular Culture,” Keynote talk, Energy and the Arts conference, University of New South Wales, Australia.

June 24, 2015. “Shamanism, Abjection, Possession, Tantra.” A talk at the Copycat Academy at Luminato Festival, Toronto.

April 18, 2015. Keynote talk on digital copying, Extending Play Conference, Rutgers University Media Studies.

April 12, 2015. “On Practice”, w. Gabriel Levine. Performance Philosophy Conference, Chicago.

March 14, 2015, “Is There a Life Beyond Mimesis?” Keynote talk, Re-Originality: Curation, Plagiarism and Cultures of Appropriation conference, Concordia U., Montreal.

Jan. 31, 2015. “Between Love and Violence: Sonic Subcultures and the Politics of Vibration”, Transmediale Festival 2015: UN TUNE, Berlin. **Audio: here**.

Nov. 7-9, 2014. “Towards a Reichian Theory of Networks.” Tuning Speculation Conference #2. York University, Toronto.

Nov. 4, 2014. “Curating After WikiLeaks”. Keynote talk at Curating in the Haze of Empires Conference, Ontario Association of Art Galleries, Toronto.

Nov. 1, 2014. “Hot/Cold/Hot”. A talk on immersive vibratory environments with Christie Pearson, at Sauna Symposium, hosted by C Magazine, Hart House Farm, Caledon Hills, Ontario.

Oct. 18, 2014. A conversation with DJ/Rupture a.k.a. Jace Clayton. X-Avant Festival, The Music Gallery, Toronto.

Sept. 23, 2014. A conversation on the Beats and photography with Louis Kaplan. University of Toronto Art Center, Hart House, Toronto. Watch video.

Aug. 7, 2014. Chaired a panel on “Cultures of Nightlife” at the Urban Night Colloquium, McGill University/ Casa di Popolo, Montréal.

June 12, 2014. Talk on Shamanism and the Avant Garde, Luminato Festival, Toronto.

Nov. 1-2, 2013. “The Drone of the Real: On the Sound-works of Catherine Christer Hennix”. York University, Toronto, Tuning Speculation Conference. Watch video.

Oct. 14, 2013. “The Politics of Vibration in Recent Hip-Hop Videos” at SUNY Buffalo, Visual Studies Speaker Series.

April 2013. “Sex, Death and Vibration in Recent HipHop Videos,” Media And Information Studies Dept. Speaker Series, University of Western Ontario.

March 2013. “Meditations in an Emergency: On the Apparent Destruction of My MP3 Collection”, Lake Forest Literary Festival, Illinois.

January 2013. “The Politics of Vibration” at McMaster University, Hamilton. Watch video.

April 2013. “Drugs and Object Oriented Ontologies in the Work of Philip K. Dick,” American Comparative Literature Association Conference, University of Toronto.

Sept. 2012. “Odd Future/Abject Future: On the Politics of Vibration”, Art Criticism and Writing series, School of Visual Arts, New York.

May 2012. ”Depropriation: The Real Pirate’s Dilemma”, Multidisciplinary Approaches to Intellectual Property Law Workshop, U. Ottawa.

April 2012. “Tyler, the Creator’s “Yonkers” and the Politics of Vibration, Sound Workshop, Cornell U.

Dec. 2011. ”Depropriation: The Real Pirate’s Dilemma”, Postcolonial Piracy conference, U. Potsdam, Germany.

Oct. 2011. Panel on Sound Cultures, Sounding Cultures: From Performance to Politics Conference, Cornell U.

August 2011. 2011 Annual Report on Drugs and Creativity. A keynote given at Creative Capital | The Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant Program‘s Arts Writers Convening event in Philadelphia.

April 2011. “From Louis Vuitton to Bottega Veneta: Capitalism and Copying After the “It” Bag”, Schulich Business School Speaker Series, York U.

March 2011. “Interdependence and Imitation”, Center of Gravity Speaker Series, Toronto.

March 2011. “Tickets That Exploded: Materialist and Mystical Models of Self Dissolution in the Beats”, keynote at Altered States Conference, University of Lausanne, Switzerland.

March 2011. “Buddhism After Badiou”, Middlesex University, Philosophy Dept. Speaker Series, UK.

February 2011. “Copying as Intrusion”, Fourth Annual Blackwoods Gallery Talk co-presented by the Department of Visual Studies, University of Toronto, Mississauga.

June 2009. Carnival Folklore Resurrection in the Age of Globalization. A talk given at CTM Festival‘s STRUCTURES NODE 1 – Global Alchemy event in Berlin, Germany.

April 2009. “Law, Appropriation, Sound”, Yage Tapes: Shamanism and Intellectual Property in Colombia; Theorist and Jurists Series, Baldy Center for Law and Social Policy, SUNY Buffalo.

May 2007. “Alternative Modernities? Thoughts on Asian Religions and Twentieth Century Literature”, Workshop on Diasporic Asian Religions, National University of Singapore.

And more ……..

Journalism

“Zillions of Things Become One Thing: An Interview with Catherine Christer Hennix”, The Brooklyn Rail, Sept/Oct. 2020. Part 1. Part 2.

“Catherine Christer Hennix: An Interview”, Blank Forms, No. 3 (2019).

“A Tribe Called Red“, The Wire, 423, May 2019.

“Liberation” (for the I Love John Giorno exhibition), Brooklyn Rail (July 2017).

“Moroccan Trance: A Primer”, The Wire, 397, (Mar. 2017).

“Sam Shalabi and Experimental Music in Cairo after Tahrir Square”, The Wire, 357 (Nov. 2013).

“Talking Dirty” in The Wire, 352 (June 2013).

“Music Appreciation: Drone” in Boing Boing (2012).

“Music Appreciation: Global Bass” in Boing Boing (2012).

“Collateral Damage: Marcus Boon” in The Wire 333 (November 2011).

“Kenneth Goldsmith” in BOMB 117 (Fall 2011).

“Epiphany/Vuvuzela” in The Wire 323 (January 2011).

“Shaking the Foundations: An Interview with Catherine Christer Hennix” in The Wire 320 (October 2010).

“Meditation Music” in The Wire 297 (November 2008).

“Tongue Dipped In Wisdom: An Interview with John Giorno” in BOMB 105 (Fall 2008).

“Ashram Lit” with Christie Pearson in Ascent Magazine 37 (Spring 2008). [pdf]

“Four Seismic Musical Events” in The Wire 277 (March 2007).

“FM3” in The Wire 268 (July 2006).

“Global Ear: Toronto” in The Wire 263 (January 2006).

“Philip Corner” in The Wire 244 (June 2004).

“Tim Hecker: Fishy Business” in The Wire 237 (November 2003).

“Sam Shalabi: The Matrix Imploded” in The Wire 233 (July 2003).

“Sarah Peebles: Electronic Bug Culture” in The Wire 231 (May 2003).

“Michael Snow” in The Wire 230 (April 2003).

“Global Ear: Marrakech” in The Wire 222 (August 2002).

“Ocean of Sound (Ocean of Silence): Siri Karunamayee talks to Marcus Boon” in Ascent Magazine 14 (Summer 2002).

“Ether Talk” in The Wire 220 (June 2002).

“12k” in The Wire 218 (April 2002).

“Mexico’s Sweet Gold” (March 2002).

“Jon Hassell: There Was No Avant Garde” in Hungry Ghost (January 2002).

“Charlemagne Palestine: Searching for the Golden Sound” in Hungry Ghost (January 2002).

“Badawi: Tomorrow’s Warrior” in The Wire 215 (January 2002).

“Is There Music After 091101?” in The Wire 213 (November 2001).

“Henry Flynt: American Gothic” in The Wire 212 (October 2001).

“09:16:01 NYC” in Hungry Ghost (September 16, 2002).

“09:12:01 NYC” in Hungry Ghost (September 12, 2002).

“Pandit Pran Nath” in The Wire 211 (September 2001).

“An Interview with Sri Karunamayee” in Ascent (2002)

“Four Seismic Musical Events” in The Wire (2007)

“FM3” in The Wire (2006).

“Gamelan in the New World“, sleevenotes to the Locust reissue of their recordings.

“Meditation Music” in The Wire (2008).

“Mexico’s Sweet Gold“, unpublished (2002).

“Sublime Frequencies Ethnopsychedelic Montages“, in Electronic Book Review (2006).

“Global Ear Toronto: On Rat Drifting Records” in The Wire (2002)

“1970’s Algerian Proto-Rai Underground: A Review” in The Wire (2008)

“Akira Rabelais: Spellewauerynsherde” for Samadhi Sound (2004).

“Bird Show – Lightning Ghost: A Review” in Signal to Noise (2006).

“Black Mirror: Reflections in Global Musics: A review“, (early 2000s).

“Harold Budd’s Avalon Sutra: A Press Release” for Samadhi Sound (2004).

“Mix Tape: The Art of Cassette Culture: A Review” in The Wire (2005).

“Two Rat Drifting Recordings: On Eric Chenaux and Ryan Driver” in Signal to Noise (2008).

“David Toop – Sound Body: A Press Release” for Samadhi Sound (2007).

“Kenneth Goldsmith, Day: 2 Reviews“, unpublished.

“Derek Bailey – To Play“, a press release for Samadhi Sound (2006)

“DIY: The Rise of Lo Fi Culture“, book review, Signal to Noise (2007).

“Eccentric Soul: Mighty Mike Lenaburg and Good God! A Gospel-Funk Hymnal“, a review, The Wire (2007).

“Eliane Radigue – Mila’s Journey Inspired by a Dream“, a review, The Wire.

“Eric Chenaux – Dull Lights“, a review, The Wire (2006).

“Éthiopiques, Volumes 22 & 23: A Review“, The Wire (2008).

“Henry Flynt, Purified by the Fire: A Review“, in Signal to Noise.

“FM3 + Dou Wei, Hou Guan Yin: A Review“, Signal to Noise (2006).

“Give Me Love: Songs of the Brokenhearted – Baghdad, 1925-9: A Review“, The Wire (2008).

“Group Inerane – Guitars From Agadez“, a review, The Wire (2007).

“Georges Gurdjieff – Harmonic Development: The Complete Harmonium Recordings 1948-1949: A Review“, The Wire (2005).

“Kath Bloom and Loren Connors – Sing the Children Over”

“Lula Côrtes and Zé Ramalho – Paêbirú”

“rappin”

“Richard Youngs and Alex Neilson – Partick Rain Dance”

“sad hits”

“The Silt – Earlier Ways of Wandering”

“Tsegué”

“wada”

Essays

“Laudanum” in The Oxford Companion to Spirits and Cocktails, ed. David Wondrich et al (Oxford University Press, forthcoming).

“On Pandit Pran Nath: An Interview with Terry Riley » in Ecstatic Aperture: Perspectives on the Life and Work of Terry Riley, ed. Vincent de Roguin (Rennes, France, Shelter Press, forthcoming).

“Catherine Christer Hennix, the Practice of Music and Modal Ontology” in Practical Aesthetics, ed. Bernd Herzogenrath (Bloomsbury, 2021).

“A place where the unknown past and the emergent future meet in a vibrating soundless hum: Thoughts on Energy and the Contemporary,” in Energy and the Arts, ed. Douglas Kahn (MIT Press, 2019).

“Towards A Taxonomy of Copying Practices in Museums” in Museum: A Culture of Copies, ed. Brita Brenna (Routledge, 2019).

“Depropriation” in Originalcopy: Post-Digital Strategies of Appropriation, ed. Franz Thalmair et al (University of Applied Arts, Vienna, 2018).

— reprinted in Radical Cut-Up: Nothing is Original, ed. Lukas Feireiss (Amsterdam, Sandberg/Sternberg Press, 2019).

“The Replication of Ideology: A Conversation Between Adrienne Shaw and Marcus Boon“, Journal of Games Criticism, 2016.

“On the Bowerbird, the Difunta Corea and Some Architectures of Sense: An Interview with Alphonso Lingis.” Scapegoat, Eros Issue, spring 2016.

“Between Scanner and Object: Drugs and Ontology in Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly,” in The World According to Philip K. Dick, eds. Alexander Dunst and Stefan Schlensag (Palgrave, 2015).

“Depropriation: The Real Pirate’s Dilemma” in Postcolonial Piracy, eds. Lars Eckstein and Anja Schwarz (Bloomsbury Press, 2015).

“Structures of Sharing: Depropriation and Intellectual Property Law”, Intellectual Property for the 21st Century: Interdisciplinary Approaches, ed. Madelaine Saginur, Teresa Scassa and Mistrale Goudreau (Irwin Law, 2014).

“From the Right to Copy to Practices of Copying” in Dynamic Fair Dealing: Creative Canadian Culture Online, eds. Rosemary Coombe and Darren Wershler, (University of Toronto Press, 2014).

“Meditations in an Emergency: On the Apparent Destruction of my MP3 Collection” in Contemporary collecting: Objects, Practices and the Fate of Things, edited by David Banash and Kevin Moist (Scarecrow, 2013).

“One Nation Under a Groove? Music, Sonic Borders and the Politics of Vibration“, in Sounding Out! (Feb. 2013).

Review of Semblance and Event: Activist Philosophy and the Occurrent Arts in SCAPEGOAT: Architecture | Landscape | Political Economy 3 (2012).

“Digital Mana: On the Source of the Infinite Proliferation of Mutant Copies in Contemporary Culture” in Cutting Across Media: Interventionist Collage and the Politics of Appropriation, ed. Kembrew McLeod and Rudy Kuenzli (Duke UP, 2011).

“Erik’s Trip“, Introduction to Erik Davis’ Nomad Codes: Adventures in Modern Esoteria (Yeti Books, 2010).

“John Giorno’s Buddhist Poetics of Transgression” in The Emergence of Buddhist American Literature ed. John Whalen-Bridge and Gary Storhoff (SUNY Press, 2009).

“A Conversation: An exchange between David Sylvian & Marcus Boon” in Manafone (August 2009).

“Sound Commitments: Avant-garde Music and the Sixties: A Review” in Signal to Noise 54.3 (Summer 2009).

Introduction to Subduing Demons in America: The Selected Poems of John Giorno, ed. Boon (Soft Skull, 2008).

“On Appropriation” in CR: The New Centennial Review 7.1 (2007).

Introduction to Walter Benjamin’s On Hashish, trans. Howard Eiland (Harvard University Press, 2006).

“Sublime Frequencies’ Ethnopsychedelic Montages” in Electronic Book Review‘s music/sound/noise issue (2006).

“Philip Corner, Gamelan Son of Lion and ‘Gamelan in the New World” liner notes for The Complete Gamelan in the New World CD re-issue (Locust Music, 2004).

“The Eternal Drone” in Undercurrents: The Hidden Wiring of Modern Music ed. Rob Young (Continuum, 2003).

“Dark Angels” in Hungry Ghost (2002).

“Naming the Enemy: AIDS Research, Contagion and the Discovery of HIV” in Cultronix 4 (1996).

The Eternal Drone

This essay was originally published in Undercurrents: The Hidden Wiring of Modern Music in 2003. (To read more of my published essays, click here.)

“Boredom is the dream bird that hatches the egg of experience. A rustling in the leaves drives him away.”

Walter Benjamin

Once upon a time, there were enormous halls, which could be found in many cities, where you could go and listen to the raw blast of Just Intonation tuned drone music every week, under a cascade of multi-colored lights. It was said by those who had visited these halls that this was the loudest sound in the world, and people crowded into these halls week after week, to be saturated in sound and light, and have ecstatic experiences. I am not talking about the lofts of downtown Manhattan where in the early 1960s, La Monte Young, John Cale, Tony Conrad and friends created the colossal drones of the Theater of Eternal Music, from which the Velvet Underground, My Bloody Valentine and most of what is best in late twentieth century Western culture issued forth. Nor am I talking about the communes and basements of West Germany and Switzerland in the 1970s, where Can, Amon Duul and Ashra Tempel and company took keyboard driven raga rock into interstellar overdrive. I am not even talking about the legendary drum and bass, techno and trance clubs that sprung up all over the world in the 1990s, wherever you could find a power socket or a generator, where synthesizer-created drones provided a trance-inducing bedrock for a Dionysian festival of percussive and pharmacological experiment.

There was no electricity in the cathedrals of medieval Europe, like Notre Dame in Paris, where enormous pedal organs tuned to specific harmonically related pitches accompanied drone or sustained tone based vocal recitations written by composers such as Leonin and Perotin, or the Gregorian chant masters. Operated pneumatically, using a bellows, the organs were vast, and the cathedral functioned as a resonant chamber that amplified the organ so that the space was saturated with rich overtones, as strange psychedelic color effects created by the stained glass windows illuminated the walls and the faces of the crowd. An English monk, Wulstan, described the newly built Winchester church organ in 960 AD: “Twice six bellows are ranged in a row, and fourteen lie below … worked by seventy strong men … the music of the pipes is heard throughout the town, and the flying fame thereof is gone out over the whole country.” “No one,” it was said, “was able to draw near and hear the sound, but that he had to stop with his hands his gaping ears.”

This was not the underground. This was at the very center of European culture – the DisneyWorld of its time. But with the growing use of the keyboard in the fourteenth century, and the gradual adoption of standardized tuning systems, such as the equal tempered scale which has dominated Western music from the eighteenth century until this day, the drone disappeared from view. Because the equal tempered scale is slightly out of tune from the point of view of the natural harmonics of sound (it “equalizes” the differences in pitch between notes on a keyboard to simplify and standardize tuning), the matrix of harmonies that makes the drone so pleasing when a Just Intonation tuning system (i.e. one using the natural harmonics of sound, and the laws that determine which pitches are in tune with each other) is used, is lost. The word drone became an insult, an indication of boredom, repetitiveness, lack of differentiation. What happened?

It’s true: drones remain boring, irritating even to many people. When Lou Reed issued his dronework homage to La Monte Young and Xenakis, Metal Machine Music in 1976, it was reviled by most of the unsuspecting fans who bought it expecting the catchy pop tunes of Transformer. If by drones we mean music that is built around a sustained tone or tones, there is something about a sound that does not shift, something about the experience of a sound heard for an extended duration that nags at consciousness, interrupts the pleasure it takes in the infinite variety of notes, combinations and changes. Or pulls it towards something more fundamental. Which is more important? That which changes, or that which stays the same? It need not be a question of either/or. In fact, it cannot be. We cannot block out the fact that we exist as finite beings within eternity or infinity – that’s how it is, whether we like it or not. But at least when it comes to man-made sounds, to music, there is no such thing as a music that remains the same for an infinite duration. Even La Monte Young’s extended tone pieces, such as his sinewave tone pieces from the 1960s like Drift Studies, or the current 8 year Dream House: Sound and Light installation started and will stop — although, Young has made the silences at the beginning and end of some of his compositions part of the piece, thus extending them into eternity, and sound’s “eternal return”. And if the music did not stop, we would stop, or change. We are changing as we listen, both physically, as the cells of our body grow, die and are replaced, and mentally, as our concentration shifts from one aspect of the sound we are listening to, to another, as our position in the room subtly shifts, resulting in different combinations of tones heard.

Beneath all that changes, is there a constant sound that is to be heard? Can we experience eternity right now, in sound? In India, one way of saying drone is “Nada Brahma” – “God is sound”, or “sound is God”. What we call music is ahata nad – “the struck sound”, but behind, inside this sound is anahata nad – “the unstruck sound”: the sound of silence. The relationship between the struck and the unstruck sound can be modeled in different ways. Indeed, at the moment when the drone re-emerged after World War 2 in America, with La Monte Young’s Trio for Strings (1958), we can see divergent but complementary models very clearly in John Cage and La Monte Young’s attitudes to sound. As Kyle Gann has written: “In Cage’s aesthetic, individual musical works are metaphorically excerpts from the cacophonous roar of all sounds heard or imagined. Young’s archetype, equally fundamental, attempts to make audible the opposite pole: the basic tone from which all possible sounds emanate as overtones. If Cage stood for Zen, multiplicity, and becoming, Young stands for yoga, singularity and being.”

Cage’s 4’ 33” (1952), with its “silent” non-performance at the piano forces the listener to become aware of the persistent omnipresence of sounds within silence and vice versa, both inside the listener and in the environment of the concert hall. Young’s Composition No. 7 (1960), which consists of a notated B and F# together with the instruction “to be held for a long time”, provides a single constant sound that changes as what Young has called “listening in the present tense” develops. Freed, at least temporarily, from the distraction of change and time, the listener enters the stream of the sound itself and discovers that what seemed to be a single drone sound shifts and changes as the listener scans and focuses on different parts of it, opening up into a universe of overtones, microtones and combination tones. Of course, this experience is entirely dependent on correct tuning. A B and a F# on a conventionally tuned piano won’t sound that amazing – nor will a drone that’s tuned this way. Young’s interest in sustained tones and Just Intonation, which he grew increasingly fascinated by in the early 1960s, support each other, because Just Intonation brings out the full spectrum of overtones which make drones so satisfying to the ear. This music may be “minimalist” in terms of instructions, but the resulting sound, as Terry Riley quipped is actually “maximal” – or, to use a word that Young says he once preferred, it’s “meta-music”.

Why has the drone become such a key part of the contemporary music scene, from Keiji Haino’s hurdy gurdy and fx pedaled guitars to the spiritualized pop of Madonna, the ecstatic jazz of Alice Coltrane or film soundtracks such as Ligeti’s for 2001: A Space Odyssey? Why do we want to be immersed in what David Toop has called the ocean of sound? Marshall McLuhan defined the electronic universe that opened up after World War 2 as being one of participation, immersion, acoustics, in contrast to the predominately visual culture that dominated the west for the last 500 years, which was a culture of spectators, distance and writing. Drones, embodying and manifesting universal principles of sound and vibration, in a fundamental sense belong to nobody, and invite a sense of shared participation, collective endeavor and experience that is very attractive to us. It is this aesthetic of participation that connects them with the punk scene. In 1976, Mark P. in Sniffing Glue drew a chart with 3 chords on it and said “now go out and form a band” – and within a couple of years, guitar bands like Wire, and its side projects like Dome had spiraled off from these chords into sustained-tone drone space. But today, even one of those chords might be too much sound. “If you ever thought feedback was the best thing that ever happened to the guitar, well, Lou just got rid of the guitars,” quipped Lester Bangs regarding Metal Machine Music.

Just as the drone can cause powerful shifts in individual consciousness, so it also re-organizes traditional hierarchies of music production and consumption. Drones are ill-suited to commercial recording formats such as the CD, due to their length, the way they rely on the acoustics of the room in which they’re produced, and the paradoxically intimate relationship with visual culture that they often have. The CD of Alvin Lucier’s Music on a Long Thin Wire, with it’s warm resonant humming tone, is gorgeous, but it hardly captures the original sound installation from which the sound recording was made – just as no sound recording of La Monte Young’s work can capture Marian Zazeela’s complementary light sculptures, and no movie soundtrack recording can supply the experience of actually seeing the film it comes from.

The battle between Young, Zazeela, Cale and Conrad and over who “owns” the recordings of the Theater of Eternal Music rehearsals and performances embodies basic contradictions contained in the rediscovery of the drone in Western culture. Young discovered sustained tones in a sense that could be covered by traditional notions of authorship and copyright, but, as he himself once asked, how do you copyright a relationship between two pitches? Or for that matter the mathematical principles governing just intonation pitch relationships which Tony Conrad pointed out to Young in 1964? From the point of view of the performers, the creation of drones, even according to someone else’s instructions, feels like an intense collective experience and endeavor. Newer groups like Vibracathedral Orchestra, or Bardo Pond, or the Boredoms have returned to the tribal spirit of drone creation, in which drones are collectively improvised. Meanwhile, the profusion of electronic drone based musics, of microsound, lowercase, minimalist house, ambient etc. on labels like 12k, Mille Plateaux or raster extends this idea of community in a different way, as the line between producer and consumer is blurred by limited edition CDs and CD-Rs, which are mostly bought or exchanged by those who are part of the scene, and themselves making drone based music.

Drones are everywhere, in beehives, the ocean, the atom and the crowd. La Monte Young speaks of tuning tamburas to a 60 hz pitch, which is the speed at which electricity is delivered in the USA (in Europe it’s 50 hz). Unless we live totally off the grid, our lives are tuned to this sound pitch, like instruments. The word “vibration” has come to stand in for all that people find loathsome about hippy, New Age, California spiritual vagueness, but, as a series of dogmatic but useful books like Joachim-Ernst Berendt’s Nada Brahma: The World is Sound and Peter Michael Hamel’s Through Music to the Self have documented, from the point of view of physics, everything vibrates and therefore can be said to exist as sound, rather than merely “having a sound”.

The word vibration entered sixties culture through Sufism, and in particular through the work of an Indian musician and philosopher Sufi Hazrat Inayat Khan, who traveled to New York for the first time in 1910. In his classic book, The Mysticism of Music, Sound and Word, Khan sets out a doctrine in which sound, movement and form emerge out of silence: “every motion that springs forth from this silent life is a vibration and a creator of vibrations.” It’s important to state this clearly: according to Khan, matter and solid objects are manifestations of the power of vibration and sound, and not vice versa. Sound comes first, not matter. So, the universe is sound, and the drone, which sustains a particular set of vibrations and sound frequencies in time, has a very close relationship to what we are, to our environment, and to the unseen world that sustains us. Khan: “With the music of the Absolute the bass, the undertone, is going on continuously; but on the surface beneath the various keys of all the instruments of nature’s music, the undertone is hidden and subdued. Every being with life comes to the surface hidden and subdued. Every being with life comes to the surface and again returns whence it came, as each note has its return to the ocean of sound. The undertone of this existence is the loudest and the softest, the highest and the lowest; it overwhelms all instruments of soft or loud, high or low tone, until all gradually merge in it; this undertone always is, and always will be.” The traditional name given to this never-ending undertone, which has been repeated by musicians from Coltrane and Can to Anti-Pop Consortium is OM, and by saying OM, the monk or the musician tunes into perfect sound forever.

Drones can embody the vastness of the ocean of sound, but they also provide a grid, or thread, through which it can be navigated. La Monte Young has talked about using his sustained tone pieces as a way of sustaining or producing a particular mood by stimulating the nervous system continually with a specific set of sound vibrations – thus providing a constant from which the mind can move, back and forth. In a recent interview, one of Pandit Pran Nath’s disciples, Indian devotional singer Sri Karunamayee pointed out that the tambura, the four stringed drone instrument that accompanies most Indian classical music performances “gives you a feeling of groundedness, so you do not get lost as in Western music. It is said that even Saraswati, goddess of wisdom and learning and music, when she enters the Nada Brahma, the ocean of sound, feels that it is so impenetrable, so profound, and is concerned less she, the goddess of music may be lost, inundated by it. So she places two gourds around her, in the form of Veena, and then she is guided by them into it.” Indian singers love to say that to be between two tamburas is heaven. They mean it literally, for the correctly tuned and amplified tambura contains a world of infinite pitch relationships. And to be perfectly in tune with universal vibration means to be one with God.

Do we have to believe in the drone’s spiritual qualities in order to experience them? The answer is no. Although in the Christian world, the sacred is thought of primarily as a matter of faith and belief, there is another view of the sacred that is concerned with practice, and the use of sacred technologies. Although the drone has often been used as a sacred technology, both in the East and the West, there is nothing that says it has to be so. Indeed, like all former sacred technologies in the modern era, including drugs, dance and ritual, erotic play or asceticism, musicians have appropriated and reconfigured the drone’s power in many ways that question traditional notions of the sacred. It has been said repeatedly that drones are, in the words of a Spacemen 3 record for “taking drugs to make music to take drugs to.” The Theater of Eternal Music were famous for their use of hashish and other substances, which allowed for extended periods of concentration and sensitization to micro-intervals. The Velvet Underground made explicit this link, with Cale’s droning viola underpinning Reed’s vocal on “Heroin”. More recently, Coil, in their Time Machines, have produced a series of long drone pieces, each named after one of the psychedelics. Conversely, writers like René Daumal who have described their drug experiences, have reported experiencing their own identities as sustained tones.

In fact the drone is a perfect vehicle for expressing alienation from conventional notions of the sacred – either existentially, through a cultivation of “darkness”, as Keiji Haino, dressed in black, with his hurdy gurdy and fx pedals, has done; or through a music that emphasizes mechanism and dissonance in imitation of the drone of the machinery of industrial society (hence “industrial music” and Throbbing Gristle’s early work in alienated sound). In his essay on Reed’s Metal Machine Music, Lester Bangs dwelled on the “utterly inhuman” quality of Reed’s drone, and what he saw as Reed’s deliberate attempt at negating the human for “metal” and “machines”, and of the masochistic pleasure that he and other noise lovers took in the experience of depersonalization and subjugation to the sounds of machinery. Both of these kinds of alienation are present in the dark, negative, profane spirituality that we find in various recent mutant drone subgenres: dronecore, dark ambient, “isolationist”, with their moody horror film sound.

From the modern viewpoint, drones are effective because of their relationship to the void that existentialists believe surrounds human activity. In 1927 Georges Bataille spoke of the universe as “formless”, and all of “official” human culture as an attempt to resist this fundamental fact, which reduced the cosmos to nothing more than “a spider or a gob of spit.” There is something of this quality of formlessness at work in “dark” drones, with their dissonant tones, the endless decay, distortion and degradation of pure tones, in the name of entropic noise. This formlessness, which blurs and loosens the boundaries of individual identity, could be the source of the ecstatic, “high” quality that often comes with drone music. If we take away Bataille’s existential pessimism, we can see how the formlessness of the drone leads us to use words like “abstract” or “ambient” to describe it. Indeed, the word “drone” itself is used by reviewers and musicians alike to stand in for a whole realm of musical activity that is difficult to describe using words, because drones lack the series of contrasts and shifts that give music form or definition. But does that mean that drones are truly formless, or do they embody deeper aspects of musical form?

It would be easy to say that the sacred spiritual qualities of the drone were connected with harmony, and the consonance of different pitches – thus the saccharine sweetness of New Age music with its crude harmonies – and that the profane, modern drone is connected with dissonance, with the exploration and equalization of forbidden pitch relationships. But the Just Intonation system actually moves beyond such crude distinctions. To begin with, it should be pointed out that the equal tempered scale is itself slightly out of tune, i.e. dissonant, while certain pitch combinations that are in fact in tune according to the physics of sound will sound dissonant or “flat” at first to ears that have heard nothing but music in equal temperament. Just as there is a black magic and a white magic, so there are harmonious combinations of pitches that create all kinds of moods. Think of the diversity of ragas, all of which are tuned according to just intonation scales, from the sweetness of a spring raga like Lalit to a dark, moody raga like Malkauns. There are dark harmonies as well as light ones.

In fact, the feedback which is so key to alt rock’s embrace of the drone (My Bloody Valentine’s “You Made Me Realize” and Jesus and Mary Chain’s music for example), based as it is on the amplification of the resonant frequencies from a sound source, is by definition in harmony – the feedback being composed of naturally occurring overtones within a sound. What we call noise is often merely a different kind of harmony, and the celebration of it in post-Velvets guitar culture is a celebration of harmony. That’s why it feels so good. It’s the raw power of vibrations. Keiji Haino has talked of his desire, when he does “covers” of pop songs in his Aihiyo project, to “destroy things that already existed” and to liberate sound from the “constraint” of the song. But his noise-scapes can never truly destroy song, for the pleasures of song and noise enjoy secret common ground. Haino may replace banale clichéd sound relationships with powerful fundamental ones — but these are already actually contained inside many pop songs, waiting to be liberated by amplification, by being sustained over time. When it’s at its most satisfying, noise, like pop, embodies the laws of harmony, and universal sound.

Depersonalization, alienation, spiritual kitsch, immersive sacred sound: how do we reconcile the different uses to which drones can be put? I don’t believe, as Hamel and Berendt do, that anything good can come from lecturing people that they’re bad boys and girls who should eat their spiritual spinach. I don’t believe that theory should control practice and bully it with claims of expertise either. It was Cage and the minimalists (or Louis Armstrong maybe) that finally dispatched that notion after centuries of the composer’s hegemony. We know very well by now that expertise in music is a matter of coming up with the goods. Indeed, drones have always been as much a part of folk music as sacred or “classical” music – think of the bagpipes or the many stringed instruments that have a drone string. But in this respect, the lack of understanding of what sound is that informs much of the contemporary drone scene is revealing. A new piece of software is developed, a new synth, a new trick with an fx pedal, which sounds great for a few months, is quickly passed around and imitated, and then exhausted. Nothing is learnt, just the iteration of possible combinations surrounding happy accidents, and momentary pulses of novelty. In contrast, the drone school surrounding Young, which is notable for Young’s emphasis on setting the highest possible motivation and goals, and for the depth of the scientific and musicological research that it is based on, has been endlessly productive, both in the case of Young himself, and those who’ve studied with or around him (Terry Riley, Tony Conrad, John Cale, Jon Hassell, Rhys Chatham, Arnold Dreyblatt, Michael Harrison, Henry Flynt, Catherine Christer Hennix, and at a secondary level, the Velvet Underground, Brian Eno, Glenn Branca, Sonic Youth, My Bloody Valentine, Spacemen Three etc.) – precisely because it does not rely on happy accidents, but on a knowledge of the powers of sound.

In his notes to Young-protégé Catherine Christer Hennix’s newly issued just intonation drone masterpiece, The Electric Harpsichord, Henry Flynt says: “The thrust of modern technology was to transfer the human act to the machine, to eliminate the human in favor of the machine, to study phenomena contrived to be independent of how humans perceived them. In contrast, the culture of tuning which Young transmitted by example to his acolytes let conscious discernment of an external process define the phenomenon. The next step is to seek the laws of conscious discernment or recognition of the process. And the next step is to invent a system driven by improvisation monitored by conscious apperception of the process.” In other words: don’t just let the machines run. And don’t hide behind Cage’s culture of the accident, of chance. Become conscious of what music can be, dive deeper into that vast field of sonic relationships that, at least in the west, remains almost totally unexplored.

The drone, like drugs or eroticism, cannot be easily assimilated to one side of the divide by which modernism or the avant-garde has tried to separate itself from the world of tradition. Like the psychedelics, the drone, rising out of the very heart of the modern, and its world of machines, mathematics, chemistry and so on, beckons us neither forward nor backward, but sideways, into an open field of activity that is always in dialogue with “archaic” or traditional cultures. This is an open field of shared goals and a multiplicity of experimental techniques, rather than the assumed superiority of the musicologist or the naïve poaching of the sampler posse. How vast is this field? I recently asked Hennix what the ratio of the known to the unknown is, when it comes to exploring the musical worlds contained in different just intonation based tuning systems. She laughed and said “oh, it’s about one to infinity!”

Thanks to La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela, Sri Karunamayee, Henry Flynt and Catherine Christer Hennix for their help in writing this article.