This was originally published in the November 2001 issue of The Wire. (To read more of my journalism, click here.)

In a recent seminar in New York, post 091101, French philosopher Jacques Derrida noted a link between music and forgiveness. He described an exchange between philosopher Vladimir Jankélévitch, who has written passionately of the impossibility of forgiving the Germans for the Holocaust, and a young German, who wrote an eloquent, unevasive response to Jankelevitch, describing his own feelings of guilt regarding an event that occurred before he was even born, and inviting him to visit him in Germany. Jankélévitch, who is a music lover, turned down the invitation to visit, even though the young German assured him that he would not play no German music, but only the French Debussy. Moved by the young man’s letter however, Jankelevitch, invited him to visit him in Paris, where they would “sit down together at the piano.”

No doubt, it’s premature to talk of forgiveness right now. 091101 was an unspeakable event – as I write, the bodies of those trapped in those planes and the WTC towers remain unburied, just a few miles away from me. Silence is not a word that comes to mind when one speaks of New York City – but at least for the first few days after the event, the city was almost silent. Nothing however draws pundits and speech as much as the very impossibility of speaking. And music also steps into this void of the unspeakable. But not unambiguously, as the above example in which Jankélévitch assumes that he has the power to forgive or not, suggests. One might also think of Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan’s playing of a Mendelsohn violin piece, to show his “respect” for the Jewish people he has “insulted”. Or the kitsch of Paul McCartney’s “Ebony and Ivory”, Michael Jackson’s “Black and White.” Can music act as the true expression of a forgiveness that must go beyond words – or is it a substitution for it, a convenient sleight of hand?

One of my teachers, Avital Ronell, began her first post 091101 class by ringing a bell. Another began by invoking the memory of a street musician heard on the way to school that day, belting out a tune on an old organ. At the strange shrines that sprang up spontaneously all over lower Manhattan in the days after 091101, there were the predictable post-Lennon folk singers, but also samba groups, Tibetan chants, jazz.

For myself, most of my records and CDs sit in the exact same place they were on the night of 091001. One symptom of trauma is a visceral distaste for everything that one was doing at the moment of shock. I’m sensitive to sounds, although, since I watched 091101 from my roof in Williamsburg, far enough away to see events unfold without hearing the sound, perhaps my ears are in better shape than my eyes. When I see an aircraft, I have doubts as to what it is that I am seeing: a vehicle or a bomb.

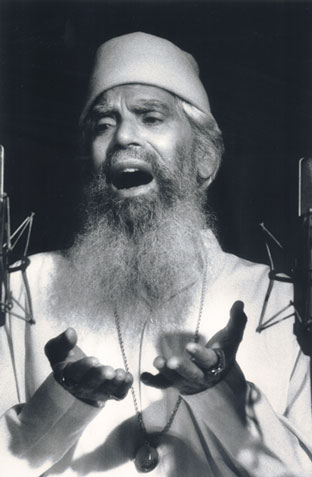

For the first weeks after 091101, the only music I was able to listen to was Indian ragas, which, with their sustained focus on a particular emotional mood, slowly penetrate consciousness until everything else falls away. And I thought about raga master Pandit Pran Nath, born a Hindu in what is now Pakistan, member of a Muslim gharana in India – precisely the kind of liminal figure we need right now, able to move between and reconcile worlds that are tragically polarized, through devotion to perfect sound.

To my surprise though, in the last week or so, I’ve found myself listening repeatedly to the queasy cold-war music of my youth: Bowie’s Low, early Pere Ubu, This Heat – avant-rock from the late-1970s that was both parasitic on, and sought to transform the prevailing culture of political polarization. Music that worked with fear, that looked for lines of flight. Does it sound gripping right now because of this, or is it that I’m going through a protective movement of regression, to “simpler” times?