I wrote a profile of minimalist composer, philosopher and blues musician Catherine Christer Hennix for The Wire last year to coincide with the release of her masterwork from the 1970s, The Electric Harpsichord. Hennix lives in Berlin these days, and has a band called The Chora(s)san Time-Court Mirage which played a series of shows this summer at the Grimmuseum. The band features the amazing Amelia Cuni, to my mind the foremost practitioner of Hindustani classical vocal music outside of the south Asian diaspora, and a master of the most austere of classical vocal styles, dhrupad. You can hear a twenty minute recording of Hennix et al on Soundcloud — the first time that anyone not living in Berlin has had a chance to hear these guys. The most obvious comparison of course is the Theater of Eternal Music, especially in later days when La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela were using sine waves, and were joined by folks like Jon Hassell. But Cuni doesn’t “just” sustain a drone tone, she moves between notes in the style of an alap singer. And there’s something about the way the sound pulsates, in a way that’s almost monstrous, that’s peculiar to Hennix. At times you can’t tell whether the sound is happening externally or actually inside your skull. The sound seems to surge, but the surge is, well, mathematical, not in the sense of something cold or formal, but in the sense of an iteration that extends to infinity … you can somehow feel or maybe hear the matrix of tones beyond what’s actually audible.

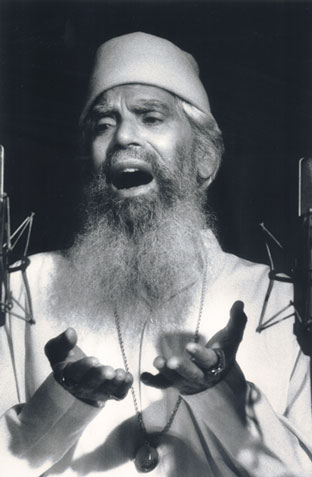

Pandit Pran Nath

This was originally published in the September 2001 issue of The Wire. (To read more of my journalism, click here.)

The sun is going down outside the magenta tinted windows of La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela’s Dream House space in Tribeca, New York. It is a summer evening in June 2001 (or 01 VI 10 7:01:00 PM NYC, to use Young’s calendrical system). The synthesized, Just Intonation tuned pitch frequencies of the dronework that usually saturates this space by day are silent, giving way to the annual memorial raga cycle in honour of Pandit Pran Nath. The minimal decor of this room, in which Young and Zazeela’s musical and spiritual guru lived from 1977-79, is transformed by a small shrine, with a picture of Pran Nath, flowers, and burning incense. Young and Zazeela sit behind a mixing desk in the centre of the room, wearing space age biker saddhu gear, and introducing a selection of raga recordings from their Dream House archives, as the small crowd – a mixture of devoted former Pran Nath students and current protegés of Young – lounge on the floor or against the wall. Unless you are lucky enough to own one of the long-unavailable recordings made by Pran Nath, this once a year event is currently the only way that you can hear what his performances sounded like.

The sun is going down outside the magenta tinted windows of La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela’s Dream House space in Tribeca, New York. It is a summer evening in June 2001 (or 01 VI 10 7:01:00 PM NYC, to use Young’s calendrical system). The synthesized, Just Intonation tuned pitch frequencies of the dronework that usually saturates this space by day are silent, giving way to the annual memorial raga cycle in honour of Pandit Pran Nath. The minimal decor of this room, in which Young and Zazeela’s musical and spiritual guru lived from 1977-79, is transformed by a small shrine, with a picture of Pran Nath, flowers, and burning incense. Young and Zazeela sit behind a mixing desk in the centre of the room, wearing space age biker saddhu gear, and introducing a selection of raga recordings from their Dream House archives, as the small crowd – a mixture of devoted former Pran Nath students and current protegés of Young – lounge on the floor or against the wall. Unless you are lucky enough to own one of the long-unavailable recordings made by Pran Nath, this once a year event is currently the only way that you can hear what his performances sounded like.

No Indian music sounds like Young’s 1970s recordings of Pran Nath. The droning tamburas are located high up in the mix, as loud, rich and powerful as vintage Theater Of Eternal Music (the experimental group Young and Zazeela formed in the mid-60s with John Cale, Tony Conrad and Angus Maclise). The tabla playing is simple but tough. The midnight raga Malkauns is traditionally said to describe a yogi beset by tempting demons while meditating. Recorded in 1976 in a SoHo studio in New York, Pran Nath’s version is unspeakably moving as he slowly chants the composition “Hare Krishna Govinda Ram” over and over, his voice winding in stretched-out, subtly nuanced glissandos that leave you begging for the next note. The 62 minute recording sounds completely traditional in it’s adherence to the slow, minimal style of the Kirana school of Indian classical music which Pran Nath belonged to, while containing in the sound itself everything that was happening in the city that year, the same year that Scorsese’s Taxi Driver hit the movie houses. Pran Nath’s voice and Young’s production turn the city into a sacred modern hyperspace, full of tension and beauty, in which anything, from Krishna to Son of Sam, can manifest.

As the music sends me into one of Young’s “drone states of mind”, I remember another sunset, a few months before, on the other side of the world. I am standing with a group of raga students at the gate of Tapkeshwar, a 5000 year old cave temple devoted to Siva, located about ten miles north of Dehra Dun in the foothills of the Indian Himalaya when the aged temple keeper turns to us and asks “Where is Terry Riley?” Around us a steady flow of pilgrims, old and young, climb down the steps to the entrance of the cave, to pour water over the Siva lingam in the heart of the temple. Not a place one would necessarily expect to find one of America’s most prolific composers of the postwar era. But over the last 30 years, Terry Riley has been a frequent visitor to this cave, where his guru and instructor in the North Indian classical tradition, Pandit Pran Nath, the man he has called “the greatest musician I have ever heard”, lived for a number of years in the 1940s.

If Riley’s presence in Tapkeshwar comes a surprise, it seems equally unlikely that Pran Nath, a reclusive, classically trained Indian singer who spent his time at Tapkeshwar living as a naked, ash covered ascetic, singing only for God, should end his days in the former New York Mercantile Exchange Building that housed Young and Zazeela’s Dream House, teaching Indian classical music to a broad spectrum of America’s avant garde musicians, including Jon Hassell, Charlemagne Palestine, Arnold Dreyblatt, Rhys Chatham, Henry Flynt, Yoshi Wada and Don Cherry. Although virtually unknown in India, Pran Nath’s devotion to purity of tone resonates through key minimalist masterworks like Young’s The Well Tuned Piano, Riley’s Just Intonation keyboard piece Descending Moonshine Dervishes, Henry Flynt’s extraordinary raga fiddling, Charlemagne Palestine’s droneworks and Jon Hassell’s entire Fourth World output.

Pran Nath was born on 3 November 1918, into a wealthy family in Lahore, Pakistan. In the early 20th century, the city was known as the flower of the Punjab, with its own rich musical tradition. According to his students, Pran Nath painted an idyllic picture of the musical culture of Lahore during this period, in which Hindu and Muslim musicians would practise outdoors in different parts of the city, congregating to perform and exchange compositions, and to hang out with their friends, the wrestlers, with whom they formed a fraternity. Many great masters including Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, and Pran Nath’s own guru Abdul Wahid Khan, lived in Lahore.

Pran Nath knew from an early age that his vocation was to be a musician, and his grandfather invited musicians into the home to perform in the evenings. But while many eminent Indian classical musicians come from families of musicians, and speak of parents whispering ragas or tal cycles to them as they sleep, Pran Nath’s mother wanted her son to pursue a law career, and, at the age of 13, gave him the choice of abandoning music or leaving home. So he left immediately, and wandered, looking for a teacher, until he came upon Abdul Wahid Khan at a music conference. Pran Nath claimed that he was able to copy every musician he heard until he encountered Wahid Khan, and on this basis decided to become his student.

Abdul Wahid Khan, along with his uncle Abdul Karim Khan, was one of the two major figures of the Kirana gharana, one of North India’s most important families of vocal music – an austere, pious man, with a powerful voice, an encyclopedic knowledge of raga, famed for his methodical elaboration of the alap, the slow improvisatory section of the raga. It is said that when he gave rare radio performances, while other singers would go home after the broadcast, Khansaheb could often be found 20 hours later, still performing the same raga. When asked once why he only practised two ragas, the morning raga Todi and the evening raga Darbari, he replied that, had the morning lasted for ever, he would have dropped the evening raga too.

Becoming a student of Wahid Khan was no easy matter. Pran Nath had no family connections, no money and was a Hindu while Wahid Khan was a devout Muslim. So, he worked for eight years as Wahid Khan’s household servant, before he was finally taken on as a disciple, at the urging of Wahid Khan’s cook. Even after that, life was not easy: Pran Nath was not allowed to practise in his guru’s presence, so he would go into the jungle at night to do so. Sometimes he was beaten if he sang a note incorrectly.

Pran Nath’s vocal abilities were recognised early on: he made his first appearance on All India Radio in 1937. However, the time that he was not serving his teacher he spent living at Tapkeshwar, naked except for a covering of ashes, and singing for God. It is likely that Pran Nath would have remained there, had Wahid Khan not ordered his student, in his guru dukshana (last request), to get married, become a householder and take his music out into the world. This Pran Nath did, moving to Delhi and marrying in 1949. That year, Wahid Khan died.

By all accounts, hearing Pran Nath in full flow at this time was an extraordinary experience. At the All India Music Conference in Delhi in 1953, attended by many of the giants of the classical music scene, Pran Nath’s performance of the rainy season raga Mian Ki Malhar stunned the 5000-strong crowd. Singer and early disciple Karunamayee recalled that when he hit the ‘sa’ note, “He held the breath of us all, collected our breath through his own breath, held it at one pitch and then let go. When he let go, we also let go, all 5000 people in the audience. It was a shock to me. All this can be done with music! And when he ended there was torrential rain! Suddenly he got up, he was very sad and frustrated and angry and said, ‘I’m not a musician, I’m only a teacher’, and walked off.”

Shattered by his guru’s death, and contemptuous of modern Indian society, Pran Nath was a moody, imposing figure during his Delhi days. He began teaching, and quickly gathered students, who were mostly reduced to silence by his skills. Singer and long-time student Sheila Dhar recalled in her memoirs: “His lessons consisted mainly in demonstrations of heavy, serious ragas in his own voice. Most of the time we listened in hypnotised states of awe. He had a way of exploring a single note in such detail that it turned from a single point or tone into a vast area that glowed like a mirage. Each of us encountered this magic at different times. Whenever it happened, it overwhelmed us like a religious experience. There was no question of our even trying to repeat this sort of thing. All we could do was to drink it all in and wait for a chance to participate in some undefined way in the distant future.”

The study of Indian classical music had undergone rapid transformation in the 20th century. The traditional guru-disciple relationship that Pran Nath had participated in became an increasingly rare thing by the middle of the century, as the patronage of the Maharajas and their courts disappeared. Radio, music festivals and recording encouraged a popularisation of classical music that favoured the light classical genres of thumri and ghazal over the intense, drawn out spaces of khayal and dhrupad, which Pran Nath was devoted to. After independence in 1947, the teaching of music was increasingly transferred to the universities. Pran Nath himself taught advanced classes in Hindustani classical vocal at Delhi University between 1960 and 1970 – a prestigious position, but one he took little pleasure in, believing that only daily, one-on-one study with a knowledgeable master over a sustained period could properly train a musician.

Among Pran Nath’s students in the 60s was Shyam Bhatnagar, an Indian emigré who ran a yoga academy in New Jersey. It was Bhatnagar who first brought recordings of Pran Nath home to America, where La Monte Young got to hear them. Young had been listening to Indian classical music since the mid-50s, and credits hearing the tambura sound on an early Ali Akbar Khan recording as one of the major influences on his groundbreaking sustained-tone pieces such as 1958’s Trio For Strings.

Among Pran Nath’s students in the 60s was Shyam Bhatnagar, an Indian emigré who ran a yoga academy in New Jersey. It was Bhatnagar who first brought recordings of Pran Nath home to America, where La Monte Young got to hear them. Young had been listening to Indian classical music since the mid-50s, and credits hearing the tambura sound on an early Ali Akbar Khan recording as one of the major influences on his groundbreaking sustained-tone pieces such as 1958’s Trio For Strings.

Throughout the 60s Young and his circle were listening to recordings of the great Indian masters. The Pran Nath recordings they heard in 1967, with their slow majestic alaps and extraordinarily precise intonation were at once new, but also uncannily similar to Young’s own music. “The fact that I was so interested in pitch relationships, the fact that I was interested in sustenance and drones, drew me toward Pandit Pran Nath,” he states. The track that fills one side of The Black Record (1969), Map of 49’s Dream The Two Systems of Eleven Sets of Galactic Intervals Ornamental Lightyears Tracery, on which Young sings shifting, raga-like phrases, backed only by a drone produced by a sinewave generator and Marian Zazeela’s voice, was “heavily influenced by Pandit Pran Nath”, according to Young. “It included drones, and pitch relationships, some of which also exist in Indian classical music. It does not proceed according to the way a raga proceeds. It has very static sections… Raga is very directional, even though it has static elements, whereas a great deal of my music really is static.” Map Of 49’s Dream… reintroduced melody to the potent, austere sustained tones favoured in The Tortoise, His Dreams and Journeys, the major work of the early 60s Theater Of Eternal Music ensemble.

In 1970, Young, Zazeela and Bhatnagar invited Pran Nath to America, after procuring grant money for him and a teaching position at the New School for Social Research in New York. In a piece written for the Village Voice in May 1970, headlined “The Sound Is God”, a euphoric Young enthused over Pran Nath’s intonation: “his singing was the most beautiful I had ever heard”. But although Young emphasized Pran Nath’s rock solid foundations in the Kirana vocal style, his interpretation of his teacher was hardly a traditional one. After praising Pran Nath’s perfect intonation and melodic abilities, the article launched into a discussion of the physics of sound, and the effect of different SOUND frequencies, measured in hertz, on neurons in the basilar membranes in the ear. “When a specific set of harmonically related frequencies is continuous or repeated,” Young concluded, “as is often the case in my music and Indian music, it could more definitively produce (or simulate) a psychological state that may be reported by the listener since the set of harmonically related frequencies will continuously trigger a specific set of the auditory neurons which in turn will continuously perform the same operation of transmitting a periodic pattern of impulses to the corresponding set of fixed points in the cerebral cortex.”

In the early 70s, Young demonstrated Pran Nath’s ability to produce and sustain very precise sound frequencies using an oscilloscope, and to this day, he is as likely to introduce a raga by expressing the tonic in hertz rather than more traditional means. The notion that all aesthetic experience, be it music, film or drug induced, is a form of programming of the nervous system, was a common one in the 60s. Inspired by Hindu scholar Alain Danielou, Young applied this idea to raga, and its concern for evoking specific moods by use of specific pitch relationships.

In May 1970, Pran Nath made his first trip to the West Coast, where he met Young’s long-time associate Terry Riley. Young, Zazeela and subsequently Riley all became formal disciples of Pran Nath, committing themselves to extensive study with him, and to providing his material needs in return for lessons. For many years, Pran Nath lived in Young and Zazeela’s loft while in New York, and in Riley’s loft in San Francisco, until in the mid-80s, in declining health after a heart attack in 1978, he moved into his own house in Berkeley, where he remained, for the most part, until his death on 13 June 1996. On both East and West Coasts, members of Sufi communities studied with Pran Nath, but in New York there was also Young and Zazeela’s gharana-like circle of downtown musicians.

During this period, Young, Zazeela and Riley, and later trumpeter Jon Hassell, accompanied Pran Nath on his return trips to India, often staying for extended periods of time to study music at a temple in Dehra Dun, where Pran Nath was temple musician to Swami Narayan Giriji, former temple keeper at Tapkeshwar. “We’d come to the temple early in the morning,” recalls Hassell, “and Swamiji would be there. I remember playing on the roof for him. He came up and sat and listened to me, with these brilliant eyes shining and smiling, seeing what I was doing on the trumpet. We would go to the market, buy two ladu [balls of hashish and almond paste] and listen to the children sing, the arti bells clapping, the swallows overhead, the muezzin singing from the minaret nearby. I mean, it was total ecstasy!” These trips gradually evolved into a yearly ritual, which has continued under the guidance of Riley and West Coast Sufi teacher Shabda Kahn, who still take groups each year to visit Pran Nath’s sacred places. There, they would study with Kirana masters like Mashkor Ali Khan, a 45 year old blood relative of Abdul Wahid Khan, who commands a vast knowledge of ragas and a fiery vocal technique.

Young, Zazeela and Riley’s commitment to Pran Nath involved more than a superficial absorption of a few Indian mannerisms. For a decade and a half, Pran Nath lived in Young and Zazeela’s loft for a good part of each year, and the New York night owls were typically required to rise at 3am each day to prepare tea for their teacher, who slept at the other end of the loft. He would then perform his riaz [practice] and give them a lesson – if he chose to. “He was the head of the household,” recalls Young. “We were not allowed to have friends. We had to give up everything – rarely did we even get to visit our parents. He was very protective of us and extremely possessive of us. But we got the reward. The reward is, if you make the guru happy, then you get the lessons.” Much of the rest of the day would be spent taking care of his financial affairs, booking students and concerts, and raising money for dowries so that his three daughters in India could get married. Riley, Young and Zazeela all sacrificed their own careers while serving Guruji (as he was affectionately known), alienating patrons who thought they should be focusing on their own work. According to Henry Flynt, John Cale once quipped that it was Pran Nath who should be taking lessons from La Monte, since he was the one with the “hard sound”.

Another part of discipleship was teaching. “He ordered us to make his own school,” Young recalls, “the Kirana School for Indian Classical Music; and then he ordered us to teach. And when I said, ‘No, Guruji, I’m not ready,’ he said, ‘you have to do as I say, it’s not up to you’.” Pran Nath made a similar demand of Riley, and Riley, Young and Zazeela have continued teaching Kirana-style Indian classical vocal to this day. Conversely, Pran Nath began teaching at Mills College in Oakland in 1973, and continued until 1984.

Pran Nath was not without his detractors. Anyone hearing him perform after 1978 would have experienced only a shadow of his former powers, since he suffered a heart attack in that year and developed Parkinson’s disease during the following decade. Even in his prime, Pran Nath was an unorthodox performer, rejecting crowd pleasing duels with tabla players, for stretched out alaps, often dwelling on the first three notes of a raga for 15 minutes or more. “Sometimes,” recalls Riley, “in the middle of the raga he would suddenly stop and start singing another raga in a performance and it would feel fine. He would maybe sing one tone that would remind him of that other raga and he’d get so inspired he’d just go off into that.” Pran Nath himself cared little about building a public reputation: in India, he snubbed critics and patrons, insulted master musicians during their performances, and had an aversion to recording and radio work. Even in America, throwing in his lot with Young and the New York avant garde or the California Sufis was hardly a guaranteed road to fame and fortune. Aside from one track recorded with The Kronos Quartet in 1993 (“Aba Kee Tayk Hamaree”/“It Is My Turn, Oh Lord”, from Short Stories), there were no collaborations with Western artists, no ‘fusion’ experiments, no compromises. He didn’t care. “This business is only for the contentment of your soul,” he would say.

Although he was a firm believer in tradition, Pran Nath himself was an outsider in India. Famous singers including Bhimsen Joshi and Salamat & Nazakat Ali Khan (“They spoiled my lessons!”, he claimed in 1972) came to him to increase their knowledge of specific ragas, yet he himself never became a celebrity. “Those who know music know his place,” says The Hindustan Times’s music critic Shanta Serbjeet Singh. “He was not a musician with a performer personality: he was too intense, too withdrawn.” According to composer Charlemagne Palestine, Pran Nath was attracted to the American avant garde because “He also was out of his culture, he rarely went home, he preferred to be in the West. As we were tormented by being a lost culture looking for our roots, he was tormented, being from a culture with enormous roots that he could no longer live in socially, as a normal member.” But despite Pran Nath’s reported fondness for Chivas Regal and watching television, he was not unduly impressed with the West either. Mathematician and composer Catherine Christer Hennix, another Pran Nath student and protegé of Young, recalls, “The only time I remember he was enthusiastic, we were in San Francisco. He liked to watch TV, and we were watching a programme about whales. He heard the whales sing and he started to cry. That was his most profound spiritual experience of the Western world.”