This was originally published in the March 2007 issue of The Wire. (To read more of my journalism, click here.)

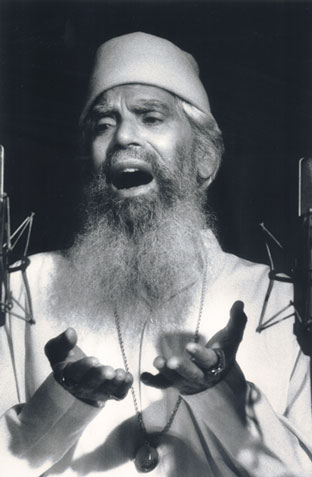

Ustad Mashkoor Ali Khan and Ustad Hafizullah Khan, Hazrat Allaudin Sabri’s shrine, Dehra Dun, India, February 2001

The idea of a live performance not intended primarily for human ears is a powerful one – and many religious traditions value the idea of singing for God. In the Sufi temples of India and Pakistan, the main sound played in the courtyard is qawalli, ecstatic vocals backed by harmoniums and hand drums, popularized by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, who also sang at all night sessions at Sufi shrines. Hazrat Allaudin Sabri was a fourteenth century Sufi master (founder of the Chishti-Sabri branch of Sufism) said to be so intense and austere that the only person who could stand near him was his musician, who sat with his back to him at some distance, so as not to be scorched by the master’s vibrations. 600 years later, Sabri’s shrine is still a very intense place, the shrine itself full of men praying, many of them in states of ecstasy. I visited the shrine with several masters of the Kirana gharana (Pandit Pran Nath’s gharana) to whom the place is sacred, including the late Ustad Hafizullah Khan, khalife of the gharana and a master sarangi player, and the remarkable singer Ustad Mashkoor Ali Khan. It was mid-day, we sat in the courtyard, a crowd gathered, kids, old men, everything between. The singing began, not qawalli, but Hindustani raga music, and the crowd listened. Hafizullah’s son Samiullah began to sing and it pierced my heart, a beautiful pure tone. I looked around and saw that I wasn’t alone. The atmosphere was one of intoxication, tears, drunkenness, a world turned upside down but gently so. I saw a man do a backflip while pacing back and forth on the marble verandah to the temple, totally entranced. I felt like I’d smoked a pound of hash. “Music can do all this!” as one of my colleagues said to me.

Concerto for Voice and Machinery, Einsturzende Neubauten, Fad Gadget etc, the ICA, London, January 1984.

There are moments at a live performance, all too rare, when reality shudders, and our ability to stand aside as objective or passive observers collapses. As we are pulled into the vortex of the event, which Antonin Artaud gave the name of the theater of cruelty, there’s a surging of mythical forces. As the field of the possible opens up, things manifest as highly charged, overlapping fragments. Power moves through us. The Concerto for Voice Machinery held at the ICA, reviled but diligent patron of the avant garde, was such a moment.

There was a cement mixer on stage. And some power drills. Einsturzende Neubauten, Fad Gadget, various friends. Some microphones. I’m not sure what we were expecting. Some noise, probably, or, more idealistically, for some new buildings to collapse.

At some point glass was tossed into the amplified cement mixer, making a tremendous sound. Someone announced that there was a secret tunnel beneath the ICA leading to Buckingham Palace. Someone else, perhaps Blixa Bargeld, started drilling into the floor of the building (or was it the stage?). The sound was intoxicating, surging purple waves of noise. Dust and sparks flew. Property was being damaged. The management tried to turn the sound off. A tug of war developed between the audience and bouncers for control of the mobile power generator which was powering the cement mixer and drill. Gasoline was leaking everywhere. Someone from the ICA tried to reason with the audience, but after a brief debate, earnestly conceded that the audience was right.

Did the police come? I don’t remember. Did anyone find the secret tunnel and make it for a secret rendezvous with the Queen? I don’t know. Outside of that theater of cruelty and that mad moment of intensity, the pigeon shit in Trafalgar Square and long night time train ride back to south London awaited us, as though nothing whatsover had happened. But for a brief moment, Einsturzende Neubauten started to live up to their name.

Schooly D circa “Saturday Night”, Public Enemy circa “Rebel Without a Pause”, 1000 Boomboxes and Car Stereos, Streets of New York City, 1985-6.

Those visiting the yuppie playground that Manhattan has become today will find it hard to imagine the New York of the early 1980s, subway trains covered with spectacular graffiti, and the streets alive with the sound of hip-hop and funk blasted from beatboxes the size of refrigerators and a thousand car stereos. The city-wide avant art extravaganza pulled off by Dondi, Rammellzee and other graf heroes found it’s analog in a world of sonic experimentation that reached a peak of gorgeous weirdness in the mid-1980s in the early tracks of Philadelphia rapper Schooly D, and the Hank Shocklee/Eric Sadler productions of Public Enemy. Schooly D’s first records such as “P.S.K. (What Does it Mean?)” and “Saturday Night” remain some of the strangest, most dusted hip-hop tracks ever made. Somehow the dull, superheavy drum machine rhythms that hold these tracks together already contain in them the distorted echo of boombox bass and drums echoing through the canyons of projects, a nihilistic ghost sound underscored by Schooly D’s mumbled, just about incomprehensible lyrics, full of menace and mysterious doped up thrills, ready to clear any pavement. It sounded even better when heard on the radio in the street, with strange audible delays resulting when the track was simultaneously broadcast on stereos one two or ten blocks away. Public Enemy’s “Rebel Without a Pause” is probably as close as we’ll ever get to having free jazz pumped at deafening volume into every public space in a city. The screeching siren like sax loop that sounded so fearsome blasting from a car rumbling across the potholes of Flatbush Avenue, bound for do or die Bed Stuy bound, actually comes “The Grunt” by the JBs. The sound ruled the streets and everybody knew it – Chuck D’s later claim that rap was a “black CNN” seems like a poor consolation prize by comparison.

La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela – New York City, The Dream House, Fall 1993 to present.

Even as other minimalists are feted globally and reissue programs make available more and more amazing archival tapes and performances, it remains next to impossible to hear recordings of the work of minimalist founder La Monte Young. A strange paradox then that all you need to do to hear Young’s work is walk up the stairs at 275 Church Street in Tribeca New York, between 2 and midnight on a Thursday or Saturday, to become fully immersed in a sound and light environment by Young and his partner, visual artist Marian Zazeela. The full title of Young’s static drone tone piece is itself too long to print here, but, to quote Young’s description, it’s “a periodic composite sound waveform environment created from sine wave components generated digitally in real time on a custom-designed Rayna interval synthesizer.” Young and Zazeela first developed the concept of the Dream House in the early 1960s as semi-permanent sound and light environments where Zazeela’s calligraphic light sculptures cast luminous shadows while Young’s drones manifest and gesture toward a world of eternal sound. The atmosphere is somewhere between the Rothko Chapel and an Indian raga house concert. No performers, just speaker stacks, a carpeted floor and pillows, magenta lights. You can move and experience the sonic grid created by the tones used in the piece, or lay still and explore the way that “tuning is a function of time” as Young says. Young says that it’s unlikely that anyone has ever experienced the feelings created by the complex cluster of just intonation tones that compose this sound environment. My own experiences in the room have not been ecstatic, in fact I find it difficult to point to any particular affective power in the sound. Yet there’s a strange magnetism to that peanut-butter thick wall of sound in that room that keeps me coming back, “eternal sound” that waits patiently for us to change and recognize it for what it is.