I’ve been working with my friend Davis Schneiderman for a number of years on a new edition of William Burroughs and Brion Gysin’s writings on the cut up. Later this year, University of Minnesota Press will publish the fruits of that research — encompassing a new edition of their classic text on the topic, The Third Mind, which will be a facsimile of the mythical unpublished 1970 Grove Press edition of that text, together with a companion volume called The Book of Methods, which will collect various key writings and statements from Burroughs and Gysin on the cut up, made over the course of their decades working together, including many hitherto unpublished texts. We will offer, for the first time, a comprehensive and chronological overview of Burroughs and Gysin’s writings on the cut up.

The Third Mind, by William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin, is a strange and enigmatic book. Long out of print after a single American edition in 1978, this eclectic offering of instructions for a material revolution has had a lasting influence on everything from punk and cyberpunk to appropriation art, new media theory and conceptual literature. The Third Mind continues to have new things to say to a generation of artists and thinkers who not only use cut-ups and fold-ins, cut-and-paste, collage and montage practices just as earlier writers used “plot” and “character,” but who also—in the present—deploy strategies from The Third Mind as a way to reveal the ubiquity of practices of collage and cut up in mainstream digital culture. Indeed, arguably we live in a moment where the cut up has triumphed — but unconsciously so, in our fragmented attention spans, our cynicism concerning the mediation of truth, and the ease with which text and image are converted to data and back again.

In The Book of Methods, a companion to The Third Mind, we propose a radical rereading of Burroughs’ and Gysin’s cut-up practices, drawing on hitherto unavailable materials by both Burroughs and Gysin, presenting the core of Burroughs’ and Gysin’s collaborative works anew for the age of digital media and the global society of the spectacle — complete with post cut up practices that include deepfakes, mass media simulation, and AI.

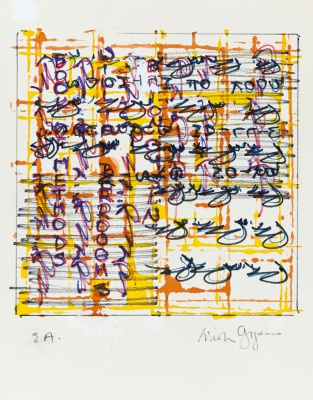

What is a cut up? Gysin discovered the technique in his studio in Paris in 1958, when he sliced through a newspaper and realized that by reading across the cut to a now exposed adjacent page, a new, “random” text was generated, with a new meaning. This cut quickly turned into an intense exploration, by both Gysin and Burroughs, of the possibilities for permutating and generating texts via processes of cutting and rearrangement. And these practices were then applied to visual images, sound recordings, film and other media. While Tristan Tzara claimed to Gysin that he was not doing anything that the dadaists hadn’t already done in World War I, Burroughs and Gysin’s ideas about the value of the cut up went far beyond Tzara’s. Burroughs in particular rapidly developed ideas of human consciousness as a cut up (in part via his involvement in Scientology), sexuality as a cut up (via the pornographic fragmentation of the drive) and reality itself as cut up (“nothing here but the recordings”).

The Book of Methods also tells the story of Burroughs and Gysin’s friendship, both in terms of their collaboration on a book expounding the cut up as method or practice, but also in terms of the ill fated publishing history of the book, which was about to be published as early as 1965, again in 1970, at varying times in the early 1970s — and then finally in 1978, at a point where much of the material was almost 20 years old. As the 1960s turned into the 1970s, Gysin’s mail to Burroughs often features an increasingly anguished “What of THE THIRD MIND??”

The cut up was untimely — but in fact 1978 was a moment where an international post-punk fan base interested in media experimentation, whether Kathy Acker, or Throbbing Gristle or the graffiti artist Rammellzee, were very much ready to respond to Burroughs’ and Gysin’s work.

The Third Mind/Book of Methods also tells a story of the importance of the Beats’ European connections and extensions, from the cut up’s genesis in the Beat Hotel on Rue Git le Coeur in Paris, to the various European writers and artists who took up the cut up, from Jeff Nuttall, to Claude Pélieu and Mary Beach, to Carl Weissner and Udo Breger — and to Gérard-Georges Lemaire, the Paris based art critic and translator of a number of Burroughs’ works, who first assembled with Brion Gysin, the texts that would compose the first actually published The Third Mind in the 1976 French book, Oeuvre croisée.