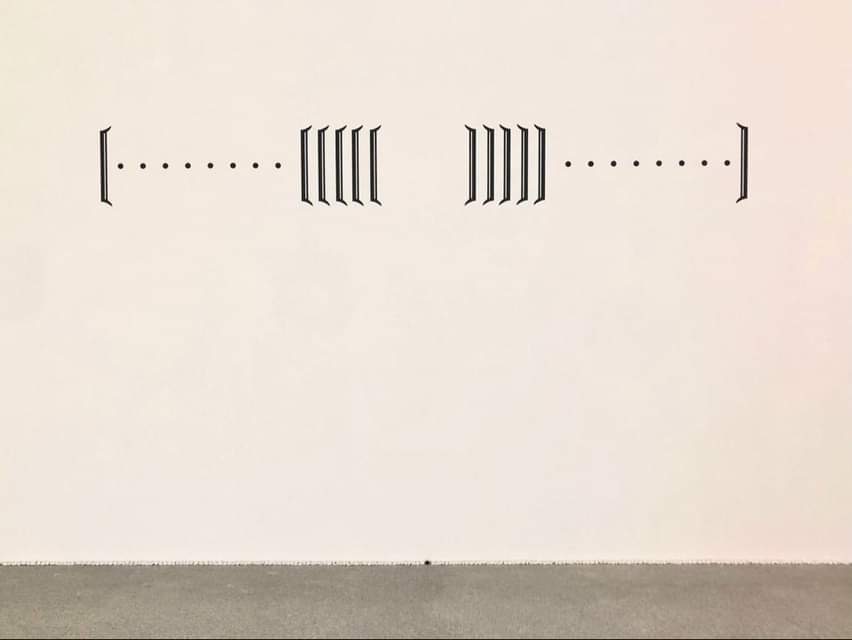

“The (MA-) Gap Theorem [Re : Yoga-57/L’etourdi]” 2021

Photo: Amadeo Schwaller

The universe vibrates. My new book, The Politics of Vibration: Music as a Cosmopolitical Practice, which will be published by Duke University Press in summer 2022, sets out a model for thinking about music as emerging out of a politics of vibration. It focuses on the work of three contemporary musicians — Hindustani classical vocalist Pandit Pran Nath, Swedish drone composer Catherine Christer Hennix and Houston-based hip-hop creator, DJ Screw, each emerging from a different but entangled set of musical traditions or scenes, whose work is ontologically instructive. Three musics characterized by slowness, much of the time then. From these particular cases, the book expands in the direction of considering the vibrational nature of music more generally. The book looks at a variety of musical examples including a Ryan Driver/Sandro Perri concert in a park in Scarborough, ethnomusicologist Jose Maceda observations concerning traditional Philippine musical instruments, Sri Karunamayee’s mental ladder of scales, Keiji Haino’s ideas of vibrational space, love and death according to Prince, Frankie Knuckles’ first visit to The Loft, Moroccan gnawa musicians in the Djemaa al Fnaa in Marrakech, John Coltrane’s famous sleevenotes to A Love Supreme, Earl Sweatshift’s alchemization of depression, and a performance by flamenco/folk master Peter Walker.

Vibration is understood in multiple ways, as a mathematical and a physical concept, as a religious or ontological force, and as a psychological/psychoanalytic determinant of subjectivity. The organization of sonic vibration that is determinant of subjectivity, a.k.a. music, is understood to be pluralistic and modal — and topological rather than phenomenological or time-based. And understanding what music is means shifting our understanding of what space is. I argue that music needs to be understood as a cosmopolitical practice, in the sense of the word “cosmopolitics” recently introduced by Isabelle Stengers — music can only be understood in relation to the worlding and forms of life that are permitted in a society, and according to decisions that a society makes concerning access to vibrational structure. I reconsider the ontology of music in the light of the practices of contemporary musicians, and I try to open up what the possibilities for a free music in a free society would be.

Even after finishing writing the book, I still find it hard to describe what I’ve written. The above paragraph is one version of it — and describes a kind of philosophical project, but the book is a lot more personal than that, since it also describes my own life, participation in different music scenes, shit that has happened, to me and those around me. And above all, the book also describes a kind of apprenticeship in music and philosophy via my introduction to the music of Pandit Pran Nath in the late 1990s, and the music and philosophy of Catherine Christer Hennix, who was a student of Pran Nath’s, in the early 2000s. While Hennix’s work has recently gained some attention thanks to Blank Forms’ publication of her selected writings in Poesy Matters/Other Matters, and various archival and new audio releases, the full complexity of Hennix’s brilliant ideas and sonic practices has not until now been documented. Hennix’s work is challenging and requires study and attention to understand her full vision of what music, mathematics, sound and ontology can do. In this book I describe my own studies and conversations with students of Pran Nath’s — and years of study and dialogue with Hennix. And I apply Hennix’s insights to musical worlds different to her own — showing how versatile and powerful and challenging her ideas are. What emerges is an idea of music as pragmatic but cosmopolitically entangled improvisation in a universe made of vibration. I explore these ideas in relation to the Black radical tradition and Houston based DJ Screw’s chopped and screwed sound. This book is also my own improvisation, in words, in that entangled universe. It is also about breaks, breaks in symmetry which give everything their particular finite forms, musical breaks and the power of repetition, mathematical modelling and its intersection with human fragility and finitude, but also the incredible breakage of/in my own world, the music scenes that I find around me, and in the lives of musicians who have cosmopolitical ambitions. This book offers a broken ontology of music — and I still don’t know if it could be otherwise.