I’ll be giving a talk about Buddhism and copying this coming Thursday, March 17th at the downtown Toronto yoga/meditation space Center of Gravity, run by author and teacher Michael Stone. The talk starts with a half hour of no-talk at 6:30 pm, after which I’ll explore some of the ways in which Buddhist philosophy and practice can illuminate contemporary issues around copying and vice versa. Center of Gravity is at 123 Bellwoods.

Buddhism After Badiou Talk at Middlesex Philosophy Dept. March 1

I’ll be giving a talk in London at the Middlesex U. Philosophy Department on Tuesday, March 1. Details here. This is one of the most progressive philosophy departments around and it’s a real honor to speak there, even more so since the department is under threat of being shut down and the site of a major struggle between faculty/students/supporters worldwide and the administration. I’ll be discussing some of my post-IPOC ideas about Buddhism and what the meaning of the word practice is, within Buddhism, but also more broadly in contemporary life. More specifically I’ll be reading the work of French philosopher Alain Badiou from a Buddhist perspective, which if you know Badiou’s post-Maoist, rigorously materialist philosophy at all, might sound like a highly improbable thing to do. The work involves rethinking Buddhism (or at least my own relation to Buddhism) as much as rethinking Badiou. I’ll save the details, which involve German Marxists Bertolt Brecht and Walter Benjamin, Tibetan modernist Gedun Choephel, Chairman Mao, Cantor’s set theory amongst others, for the talk.

Buddhism and Critical Theory: New Approaches!

I participated in a very interesting panel at the Modern Language Association meeting in Los Angeles last weekend. Three of us, Tim Morton, author of Ecology Without Nature, Eric Cazdyn, author of the soon to be published The Already Dead, and I, discussing the relation between Buddhist practice and critical theory. All of us are responding in different ways to Slavoj Zizek’s comments over the last decade concerning Buddhism. Eric explored the relationship between psychoanalytic cure, Marxist utopia and Buddhist enlightenment. Tim looked at what he calls Buddhaphobia, and read Zizek against some of Lacan’s comments on Buddhism made after his trip to Japan in the early 1960s. I explored a series of moments in modern Tibetan Buddhist history and literature in an attempt to show the ways in which Alain Badiou’s thought resonates with the history and practice of Buddhism. You can listen to the audio of the talks here.

Arthur Russell and Buddhism

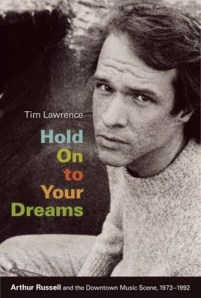

I’m just finishing Tim Lawrence’s excellent biography of Arthur Russell, Hold On To Your Dreams: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973-1992. In some ways, New York in the 1970s is starting to be very well charted territory, but the complicated web of connections between different scenes which is described in this book is still news, and Lawrence draws out these connections with the same loving detail he brought to his first book, Love Saves The Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture, 1970-1979. The book nicely complements the recent compilation of Russell protégé Peter Gordon’s Love of Life Orchestra – a group that variously featured Kathy Acker on vocals, Laurie Anderson, Rhys Chatham and many others. I think Lawrence underplays the breadth of the “mutant disco” scene – there’s no mention of Ze Records, the Bush Tetras, Arto Lindsay’s various dance projects – but maybe Russell’s path somehow didn’t intersect with “punk funk” or the other post-new wave styles that were floating around when I first visited New York in the early 1980s.

I’m just finishing Tim Lawrence’s excellent biography of Arthur Russell, Hold On To Your Dreams: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973-1992. In some ways, New York in the 1970s is starting to be very well charted territory, but the complicated web of connections between different scenes which is described in this book is still news, and Lawrence draws out these connections with the same loving detail he brought to his first book, Love Saves The Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture, 1970-1979. The book nicely complements the recent compilation of Russell protégé Peter Gordon’s Love of Life Orchestra – a group that variously featured Kathy Acker on vocals, Laurie Anderson, Rhys Chatham and many others. I think Lawrence underplays the breadth of the “mutant disco” scene – there’s no mention of Ze Records, the Bush Tetras, Arto Lindsay’s various dance projects – but maybe Russell’s path somehow didn’t intersect with “punk funk” or the other post-new wave styles that were floating around when I first visited New York in the early 1980s.

One of the surprises the book contains is that Russell was a committed Buddhist. Russell was turned on to Buddhism in San Francisco in the early 1970s when he was involved with a Theosophical sounding commune called Kailas Shugendo, and then with a Japanese Shingon priest Yuko Nonomura (Shingon being an esoteric form of Japanese Buddhism with similarities to Tibetan Vajrayana). After that he appears to have made his own way, supported by friendships with Buddhists such as Allen Ginsberg, who Russell performed with and lived in the same building as for decades. He was either incapable of orthodoxy or uninterested in it: his Buddhism more like the “spontaneous Beat zen” of the early Beats which, as Hakim Bey argues, was arguably more true to the core of Buddhist thought and practice than the more orthodox and technically authentic versions of Asian religious traditions which dominate in Europe and the Americas today.

It’s still kind of shocking to read that Russell’s early disco masterpiece “Is It All Over My Face?” was produced according to Buddhist principles:

“… Arthur planned to record a song that bubbled with the earthy, collective spontaneity of the dance floor …. In order to realize this goal, Arthur decided to run the recording sessions as a live mix and knowingly fell back on the philosophy of Chögyam Trungpa and Ginsberg, who argued for the poetic value of unmediated inspiration and lived according to the maxim “First thought best thought.””

Recording sessions took place on a full moon, because that “is a time of celestial energy, productivity, and ritual.” Definitely a key event in a generally still unwritten history of queer post-hippie spiritual practice. And although the goal of such recording sessions was generally to produce a capitalist commodity, i.e. a 12 inch single, the situation is more interesting than that kind of crude summary. For one thing, Russell was notorious for playing with time in the studio and most of the recordings he made were never finished, let alone released. As with Jack Smith’s endlessly respliced movies, Russell made rhizomes of sound that seem to have been an end in themselves. For another, the tapes produced in these recording sessions were often played at places like Nicky Siano’s Gallery or the Paradise Garage without ever being officially released, in the same way that Jamaican dub plates allowed for dancehall transmissions that would often simultaneously be kept a secret by not being labelled and packaged for the marketplace.

When you start to look, a lot of Russell’s songs have obviously Buddhist lyrics. The pre-François K version of “Go Bang” starts with the lyric “Thank you for asking me questions/you showed us the face of delusion/ to uproot the cause of confusion”. While the famous chorus line “I wanna see all my friends at once/I’d do anything to get a chance to go bang, I wanna go bang” is usually interpreted as celebrating an orgiastic dancehall sexuality, it could just as easily be talking about the Bodhisattva’s vow to bring all sentient beings together to perfect enlightenment. Nor is there necessarily a contradiction between the erotic and Buddhist meanings of the lyric since in Tantric Buddhism, bliss is an aspect of the realization of emptiness or sunyata. Russell’s dance music has a peculiar suppleness and flexibility, it feels truly at ease and open, always morphing in unexpected and delightful ways – listen to “Let’s Go Swimming” some time – and that is how the greatest Buddhist teachers I’ve met have felt too.

What could, would or should a Buddhist music sound like? Maybe the question is meaningless: a number of Buddhist artists who I’ve talked to about the relationship between their work and their Buddhist practice have bluntly denied any connection between the two, even when their music or paintings or poetry are full of explicit references to Buddhist ideas. Generally such people embrace Buddhism as a traditional practice that is self-sufficient and separate from other aspects of their “modern” lives. “Buddhist music” then would be something that sounds like music associated with a particular Buddhist tradition or culture. But that then suggests that Buddhist culture is somehow frozen within a particular set of historical forms which it must dutifully repeat in order to appear authentic.

What could, would or should a Buddhist music sound like? Maybe the question is meaningless: a number of Buddhist artists who I’ve talked to about the relationship between their work and their Buddhist practice have bluntly denied any connection between the two, even when their music or paintings or poetry are full of explicit references to Buddhist ideas. Generally such people embrace Buddhism as a traditional practice that is self-sufficient and separate from other aspects of their “modern” lives. “Buddhist music” then would be something that sounds like music associated with a particular Buddhist tradition or culture. But that then suggests that Buddhist culture is somehow frozen within a particular set of historical forms which it must dutifully repeat in order to appear authentic.

There have been a number of interesting books about Buddhism and the poetic avant-gardes, but Buddhism and contemporary music has barely been thought about. Maybe it’s because John Cage captured the brand of “Buddhist composer” so early on, although as La Monte Young once noted, “John Cage dipped into the well, but how deep did he dip?” I love Cage, and I happen to think that we have yet to find out how deep he dipped, but it’s true that his version of Buddhist music is just one version, with very particular musical decisions built around a particular set of East Asian Buddhist histories. Philip Glass seems to me a great Buddhist in terms of his support of a community of musicians (including Russell), but his music comes from other places. Although she denied it when I asked her about it, Eliane Radigue’s drones, with their emphasis on slow transformation of tonal combinations feels very meditative, and her collaboration with Robert Ashley on the life of Milarepa is stunning, reading the Tibetan saint as an old-timer in a American western. Ashley himself references Buddhism often, and his use of vernacular conversational lyrics in records like Private Lives and Automatic Writing (two of my favorite records ever ever) has an openness and spontaneity whose sources are surely in Cage, Kerouac, Ginsberg, and other practitioners of Buddhist inflected “spontaneous bop poetics.”

But Russell doesn’t really sound like any of these composers with the possible exception of Ashley. Maybe Ginsberg’s musical adventures such as First Blues, which Russell actually plays on, were important. Don Cherry was making a similarly eclectic Buddhist music throughout the 1970s, blending rock, and electric African sounds with Tibetan Buddhist chanting on records like Brown Rice and Relativity Suite. While Russell is fearless in moving between genres, he also displays a kind of warped respect for the fragile construction of those genres – which is why I was able to hear “Go Bang” for the first time in a Soho London nightclub full of strictly old school funk freaks. I think Lawrence does a great job of showing how an ethics of openness and spontaneity are expressed in Russell’s music, and in the ways that he imagined his music being used socially, to break down barriers between scenes, styles and so on. As with John Giorno’s poetry, there’s a non-coercive opening up of mental and physical spaces through montage and repetition. You don’t need to know that “this is Buddhist music” because that labeling would reify what’s going on and turn it into a mere idea of Buddhism. The “logic of sense” is loosened up in a melodic and rhythmically disciplined way — and that’s how the joys of the dancehall and the recognition of emptiness resonate.