Creative Capital/The Warhol Foundation just posted the audio of my keynote talk at the their Arts Writers convening in Philadelphia last August. They asked me to speak about drugs and creativity, and this gave me an opportunity to revisit the work I’d done on drugs and the arts in my book The Roads of Excess: A History of Writers and Drugs in the early 2000s.

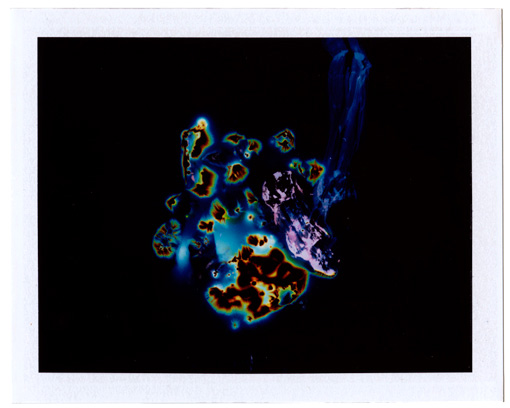

As you can hear on the audio recording, mostly my argument was that the heroic age of literary and artistic experimentation with drugs is over, even if many of the questions provoked by the existence of psychoactive substances remain unanswered. You can see it in Vancouver based artist Jeremy Shaw’s fascinating installation piece, DMT from 2004, where the gap between the noumenal quality of the experience and the banality of the images of those perhaps under the influence or their narratives is a vast one. Whatever the quality of the experience, it is basically unrepresentable, and thus beyond the sphere of art. Contrast this if you like with someone like Henri Michaux’s attempts in the 1950s and 1960s to write and draw under the influence of mescaline.

In place of this kind of art, the most interesting drug cultural artefacts have been TV shows like Breaking Bad, The Wire and Weeds. But there’s little attempt to represent drug experiences in those shows, and all the excitement and drama comes from the fact that drugs are an economic and legal proposition. It’s almost as though people now get high on business or the law, the way they used to on drugs. I find that an amazing and troubling proposition. In the talk, I looked at some of Ryan Trecartin’s recent video pieces, which are strikingly psychedelic, but whose psychedelia mimics and amplifies the self-distorting fx of corporate training videos and reality TV, and is without reference to drugs.

Talk of drugs and economy brought me back to research I’m currently doing on William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin’s collage manual, The Third Mind, and Burroughs’ still unassimilated argument that the broader lesson of drug addiction is that we almost always build our reality pictures based on what he calls “the algebra of need”. And that need can be and is manufactured — this corresponding to what Zizek and others today call ideology.

For me this opens up an interesting way of thinking about the contemporary impasse of the arts, whether writing or visual arts or for that matter music. If the presentation of reality itself happens mostly through the manufacture and manipulation of need, what can art be, other than one more form of participation in the manufacture of our need for certain kinds of reality picture? Is it a question of distinguishing between false needs and real ones? Or do “real needs” become the primary site of ideological capture … i.e. the thing that you submit to believing. Conversely, would an art that refused any discourse of need have any meaning or function whatsoever? Do we need to have needs, even beyond the biological imperatives that seem so fundamental? David Levi-Strauss asked me: why “need” and not “desire”? It was a really good question … maybe this is a very 2012 answer but it seems very difficult to think about desire today without also thinking about what limits or structures desire. It unsettles me to think about need and I think that’s a good thing.